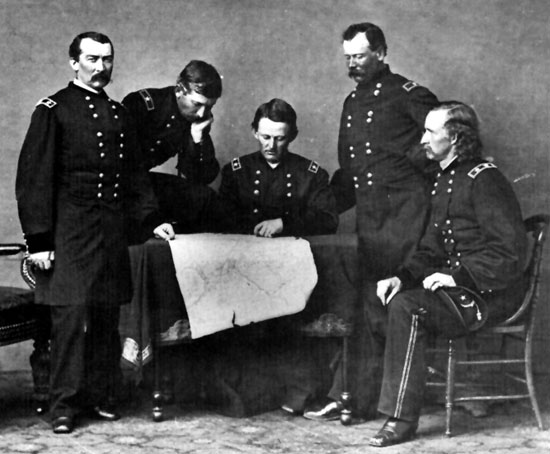

L to R, Philip Sheridan, James W. Forsyth, Wesley Merritt, Thomas C.

Devin, George Armstrong Custer, Photo by Brady Studios.

Each of the above figures, played an important part in the Indian Wars. James W. Forsyth was the

commander at Wounded Knee, Wesley Merritt was on patrol in western Nebraska and eastern Wyoming at the

time of Little Bighorn and later played an important part in the campaign against Chief Joseph, Thomas C.

Devin served in New Mexico and Arizona in the early wars against the Apache and later, 1877-78, was commander

at Ft. Laramie.

Although, the battles of the Platte River Bridge and Red Buttes were less than sucessful, the introduction of breech-loading

rifles changed the odds in two other fights, the Hayfield Fight and the Wagon Box Fight.

In the Hayfield Fight, near Ft. Smith, a haying detail consisting of 19 soldiers

and 6 civilians, under Lt. Sigismund Sternberg, equipped with breech-loading

Springfields and severl repeating rifles, successfully held off a superior force,

sustaining only 3 killed and 3 wounded.

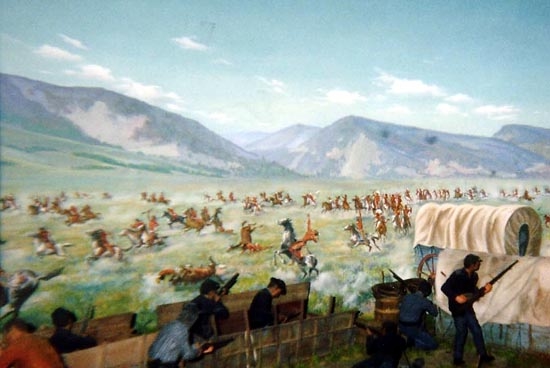

The Wagon Box Fight, portion of diorama, Jefferson National Expanision Memorial, St. Louis,

Photo by R. P. Dobson

In the Wagon Box Fight, August 2, 1867, near Ft. Kearney a detail under Capt. James Powell, barricaded behind

behind wagon bodies that had been removed from their running gear, held off

several thousand Sioux and Cheyenne, attacking in waves of several hundred at

a time, for over four hours with a loss of only 3 killed and 2 wounded. One of the three killed was

Capt. John Janness. Janneess was standing in a wagon and was ordered to get down. His last words were his response,

"I know how to fight Indians." The words were hardly out of his lips when he fell to an Indian bullet.

Site of the Wagon Box Fight. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

The Wagon Box fight is believed to have taken place on top of the knoll marked by the

line of trees. In the aftermath of the Wagon Box Fight, however, the Indians realized that they needed modern weapons. In

some instances the weaponry of the Indians was antiquated. Second Lt. George P. Belden in his

1870 BELDEN, THE WHITE CHIEF; OR, TWELVE YEARS AMONG WILD INDIANS OF THE PLAINS. FROM THE DIARIES AND MANUSCRIPTS OF GEORGE P. BELDEN, EDITED BY GEN. JAMES S. BRISBIN, U.S.A.,

recounted finding on the Fetterman Massacre site, a flintlock musket marked "London, 1777."

Through the autumn, Fort Phil Kearny remained under a state of seige. At the end of October, the Indians set fire to

the dry grass about the fort. Belden described the scene:

In the last days of the month the Indians fired the grass all around the post, and for a time we thought we should be burnt up.

The slopes of the hills, as far as the eye could reach, were covered with lines of fire, and tall sheets of flame leaped up from

the valley or run crackling through the timber. The parade ground of the garrison was lighted up at

night so one could see to read, and for a distance of many miles every tree and shrub

could be distinctly seen. The crackling of the fire sounded like the discharge of

thousands of small arms, and every few moments the bursting of heated stones would resound

over the valley, resembling the booming of distant cannon. In all my life I had never seen so

grand and imposing a sight, and never expect to witness one like it again. For three days

the flames raged over a vast extent of country, and then, having consumed all the grass

and dry trees, went out, doing us no harm, owing to the streams around the fort, which

completely checked the advance of the destroying element.

The result of the Wagon Box fight is believed to

have been the attack on Lt. Edmond R. P. Surley's train on November 2, 1867, when the train was

ambushed in a narrow ravine of Peno Creek near Goose Creek. The object of the

attack was allegedly to capture breech loading rifles and a mountain howitzer. The Indians succeeded in capturing one mule team and a wagon with its

contents. One soldier was killed and three were wounded. Among the wounded was Lt. Shurley who was

wounded in the foot. The lesson of having modern weapons was not, however, lost on the

Indians. Later at Little Bighorn, Some of the Indians had newer weapons than Custer.

With the pending completion of the Union Pacific Railroad and the relocation of

the Emigrants' Road further to the south, the necessity of

maintaining the Oregon Trail north of the Platte River was reduced. The Army, additionally, needed to

devote its attention to the southern plains. Thus,

representatives of the Indians were summoned to a great conclave at Ft. Laramie.

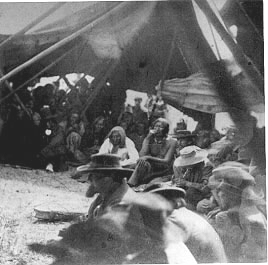

Indian Chiefs at Ft. Laramie, 1867

Left to Right: Spotted Tail, Roman Nose, Old-Man-Afraid-of-his Horses, Lone Hand, Whistling Elk, Pipe, Unidentified.

Spotted Tail was murdered in 1881 by Crow Dog. Crow Dog suspected that Spotted Tail was

stealing grazing fees and moneys paid by the railroad which rightfully belonged to the

tribe. In accordance with tribal custom, Crow Dog made appropriate restitution. Nevertheless,

Federal authorities caused Crow Dog to be arrested and tried in federal court where he was

convicted and sentenced to hang. The case went to the United States Supreme Court which held in

ex parte Kan-Gi-Shun-Ca, 3 S. Ct. 396 (1883) that federal courts had no

jurisdiction. The law as to major crimes was subsequently changed by Congress.

Crow Dog allegedly received his name as a result of being wounded in a battle and

being left for dead. The Great Spirit sent two coyotes to nurse and care for

Crow Dog. Upon his recovery the Great Spirit sent a crow to guide him home. Thus, he earned his name.

Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses smoking pipe of

peace Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses smoking pipe of

peace

Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses was a family name borne by at least three generations; thus,

Old-Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses and Young Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses. For another view of

Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses see photo to left.

Roman Nose was with Red Cloud at the Fetterman Massacre and the Battle of the Platte

River Bridge in which Caspar Collins was killed. Lone Hand was a Sioux warrier. Whistling Elk was a compatriot of

Red Cloud. Pipe was Cheyenne.

At first Red Cloud refused to participate. With, however, the agreement that the

government would close the Bozeman Trail. Red Cloud then deigned to appear for the agreement to

a Treaty in which the Indians were assured of their title to the area north of the

Platte River and Forts Reno, Kearney, and Smith were abandoned. But the treaty itself had within it the seeds of its own failure.

Col. William Bullock, manager of the Ward and Bullock store at Fort Laramie, wrote in July 1868:

I very much fear the treaty made here with the Indian will amount to nothing

more than a renewal of hostilities on the part of the Indians and a peace

never accomplished as long as Government sends such imbecils out to treat

with them as Genl. Harney and his like."

Col. Bullock may have had some reason to question Gen. Harney's competence. Following the Batttle of Blue Water Creek

discussed on a preceding page,

Harney's

military encounters included the the "Pig War" with Great Britain in 1859 in which Harney almost single-handedly caused a shooting war

between Royal Marines and U.S. forces

over the killing of a British pig rooting in an American garden on San Juan Island.

For his involvement he was officially rebuked. But San Juan Island was not the first time

Gen. Harney found himself in hot water over pigs. On July 22, 1839, during the Second Seminole War in Florida

then Lt. Col. Harney was leading

a detachment of dragoons along the Caloosahatchee River. He decided to take the day off for some hog hunting

on nearby Sanibel Island. After a full day of hunting, he returned to camp about 10:30 p.m., leaving his boat on a nearby beach. He

retired for the night without first assuring that ammunition had been distributed to the men.

The next morning he awoke to the sounds of the camp being attacked by Indians. He fled into the

woods clad only in his underwear and socks. He made his way through the thick underbrush to his boat and departed the

scene. When he returned, the overhead buzzards informed Harney of the fate of his men and his newly appointed

sutler who had accompanied the expedition. The location of the debacle is now known as

"Harney's Point." By 1861, Harney was commander of the Union

Army of the West. Suspected of being a Southern sympathizer he was relieved of command (He tried to negotiate on his

own a truce with Confederate authorities). While attempting to report to Washington, he made the mistake of

passing through Confederate territory. He was arrested by the Confederates,

held for a time and released. In 1863, he was brevetted brigadier general and

retired. For more on Harney see Fort Bridger.

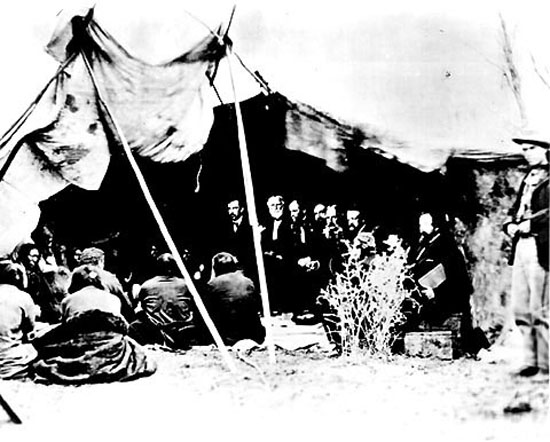

Wm. T. Sherman in council, Ft. Laramie, 1867, photo by A. Gardner

Seated in the center is Gen. Wm. S. Harney (with the white beard).

To the right is Sherman.

The photographer, Alexander Gardner, 1821-1882, during the Civil War was a part of the

Brady studios and is most famous for his photos of Antietam and the "cracked plate"

photo of Lincoln taken Feb. 5, 1865. Following the war he was the photographer for the 1867-1868 survey party

laying out a proposed route for the Union Pacific. 127 photos were taken but no complete portfolio is

now known to exist.

P.H.Sheridan, photo by C.D.Mosher, 1876

Sherman was succeeded in 1869 as commander of the Army's Division of the Missouri by Philip H. Sheridan, "Little Phil" (because of his stature, 5 Ft. 5 in., wt. 115 lbs.),

who conducted a ruthless war against the Cheyenne. Although he was adament in his denial of the expression often attributed to him

that "The only good Indian is a dead Indian", he publicly expressed that he had no remorse over the

killing of woman and children when it became necessary to attack a village. As a part of his campaign, he appointed Wm. F. Cody as chief scout of the

Fifth Cavalry. Cody was awarded, for gallantry, the Congressional Medal of Honor, revoked shortly after Cody's death.

C.D.Mosher, the photographer, modestly referring to himself as the "National Historical Photographer to Posterity" presented the above photo, with others, to the City

of Chicago to be opened at America's bicentennial in 1976. Meanwhile, Mosher made the photos available to the

public at $3.00 per dozen. As a result of the treaty, the Bozeman Trail was abandoned and Forts Reno, Smith and Kearney burned by

the Indians. However, the Treaty enabled the army to devote its attention to the southern plains.

Leaving Ft. Washakie in August 1882, Sheridan led a unit of over 120 men on an inspection of western Wyoming and southern Montana. Guided by a hunter named Geer, they became the first white

Americans to traverse the Beartooth Mountains blocking the direct route to Billings. The Beartooth Highway, opened in 1936, follows Sheridan's route.

Music this Page:

MARCHING THROUGH GEORGIA

By

Henry Clay Work

Bring the good ol' Bugle boys! We'll sing another song,

Sing it with a spirit that will start the world along,

Sing it like we used to sing it fifty thousand strong,

While we were marching through Georgia.

CHORUS:

Hurrah! Hurrah! We bring the Jubilee.

Hurrah! Hurrah! The flag that makes you free,

So we sang the chorus from Atlanta to the sea,

While we were marching through Georgia.

How the darkeys shouted when they heard the joyful sound,

How the turkeys gobbled which our commissary found,

How the sweet potatoes even started from the ground,

While we were marching through Georgia.

REPEAT CHORUS

Yes and there were Union men who wept with joyful tears,

When they saw the honored flag they had not seen for years;

Hardly could they be restrained from breaking forth in cheers,

While we were marching through Georgia.

REPEAT CHORUS

"Sherman's dashing Yankee boys will never make the coast!"

So the saucy rebels said and 'twas a handsome boast

Had they not forgot, alas! to reckon with the Host

While we were marching through Georgia.

REPEAT CHORUS

So we made a thoroughfare for freedom and her train,

Sixty miles of latitude, three hundred to the main;

Treason fled before us, for resistance was in vain

While we were marching through Georgia.

REPEAT CHORUS

Writer's Notes:

"Marching Through Georgia" was performed everywhere General Sherman went, so much so that he detested the

song. As reported by Nicholas Smith in his "Grand National Songs,"

the Young Churchman Co., New York, 1890:

So universal in its use was "Marching Through Georgia" that General Sherman heard it with.

supreme disgust. It pursued him from city to city, and from state to state; and in all

the great cities of Europe in which he was received with distinguished honors, the burden of

the music was "Marching Through Georgia." When the general attended the national encampment

of the Grand Army of the Republic in Boston in 1890, he saw from the reviewing stand two hundred

and fifty bands, and a hundred drum and fify corps pass in review; and the old warrior

stood for seven mortal hours listening to the never-ending strains of the

music which commemorates the most triumphant march of modern times. His patience collapsed,

and with a grim gravity, peculiar to him, and in language too emphatic for repetition here,

he declared that he would never attend another national encampment until every band in the

United States has signed an agreement not to play "Marching Through Georgia" in his presence.

It is, since Gen. Sherman is pictured on this page, only appropriate that we play Marching Through Georgia.

Not withstanding his aversion to the song and request that it not be played in his presence. six months later it became the centerpiece

of Sherman's funeral procession when it was played as a dirge by Patrick Sarafield Gilmore's big band in one-half time tempo. It is not reported

as to whether Sherman rolled over in his casket or protested.

The term Jubilee comes from Leviticus 25:

|

1 And the LORD spake unto Moses in mount Sinai, saying,

2 Speak unto the children of Israel, and say unto them, When ye come into the land which I give you, then shall the land keep a sabbath unto the LORD.

3 Six years thou shalt sow thy field, and six years thou shalt prune thy vineyard, and gather in the fruit thereof;

4 But in the seventh year shall be a sabbath of rest unto the land, a sabbath for the LORD: thou shalt neither sow thy field, nor prune thy vineyard.

5 That which groweth of its own accord of thy harvest thou shalt not reap, neither gather the grapes of thy vine undressed: for it is a year of rest unto the land.

6 And the sabbath of the land shall be meat for you; for thee, and for thy servant, and for thy maid, and for thy hired servant, and for thy stranger that sojourneth with thee.

7 And for thy cattle, and for the beast that are in thy land, shall all the increase thereof be meat.

8 And thou shalt number seven sabbaths of years unto thee, seven times seven years; and the space of the seven sabbaths of years shall be unto thee forty and nine years.

9 Then shalt thou cause the trumpet of the jubilee to sound on the tenth day of the seventh month, in the day of atonement shall ye make the trumpet sound throughout all your land.

10 And ye shall hallow the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof: it shall be a jubilee unto you; and ye shall return every man unto his possession, and ye shall return every man unto his family.

Next page: The Campaign of 1876.

|