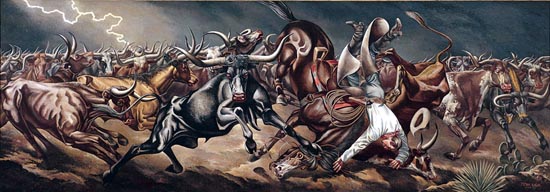

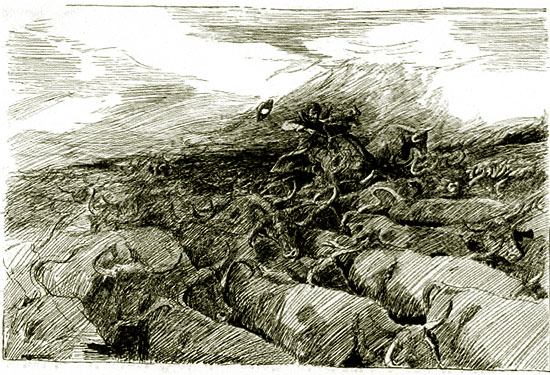

"Stampede," Chromolithograph from painting by Gean Smith, 1895.

STOMPEDE was the old Texian word, and no other cattle known to history had such a disposition

to stampede as the Longhorns. Their extraordinary wildness made them nervous, constantly expectant, habitually alert, and gave them

keenness of senses to detect objects that the most nature-sensitive of outdoors men were obtuse to.

James Frank Dobie, The Longhorns, Castle Books.

Stampede, Leslie's Illustrated News, 1881

On the trail the danger of a stampede was always present. One of the cowboys who rode the Texas or Western Trail, Edward C. "Teddy Blue" Abbott,

recalled:

"If. . .the cattle started running--you'd hear that low rumbling noise along the ground and the men on

herd wouldn't need to come in and tell you, you'd know--then you'd jump on your horse and get out there in the

lead, trying to head them and get them into a mill before they scattered to hell and

gone. It was riding at a dead run in the dark, with cut banks, and prairie dog holes all

around you, not knowing if the next jump would land you in a shallow grave.

"

Stampede, Mural, Odessa, Texas, Post Office, Federal Works Agency

C. M. "Charley" Russell wrote of one stampede in his "Longrope's Last Guard," Trails Plowed Under, Doubleday, Doran and Company, New York, 1927, pages 203-210.

He wrote of a night guard whom Russell called "Longrope." Russell wrote that the herd was about fifty miles south of Dodge.

It was quiet, two quiet. The cattle were not making the noises they make when they are

getting comfortable. It was so dark, Russell wrote,

"You couldn't find your nose with both hands." He continued: "The lighnin's quit now, an' she's darker than ever, the

breeze has died down. an' it's hotter than the hubs of hell. * * * * The ground shakes, an' they're all runnin'."

The next morning, they came across Longrope's horse, its right foreleg broken, "He's sure a sorry

sight with that fancy, full-stamped, center-fire saddle hangin's under his belly in the mud."

Writer's note: Cowboy photographer, Erwin E. Smith, "Cowboy Life in the Far Southwest," Photo-Era Magazine, January 1906, wrote that "a cow-pony

silently grazing upon a hill, with a rope dragging and a 'double half-hitch' around the pommel of the saddle is

nearly a sure proof that evil has befallen the rider." It was certainly the case with Russell's Longrope. They found in the holler of the

'royo a patch of yeller, a part of a slicker. Russell continued his narrative:

"Nobody feels like talkin'. It don't matter how rough men are —I've known 'em that never

spoke without cussin', that claimed to fear neither God, man, nor devil — but let death visit

camp an' it puts 'em thinkin'. They generally take their hats off to this old boy that comes

everywhere an' any time. He's always to ready to pilot you — willin' or not — over the long

dark trail that folks don't care to travel. He's never welcome, but you've -I got to respect him.

Writer's note: A long rope, after which Russell named the cowboy, is a sixty-foot long braided rawhide reata

traditionally used by Spanish and Mexican vaqueros. Those reatas are the original ropes used by cowboys. Like the braiding of

the rawhide, the use of a long rope is a dying art.

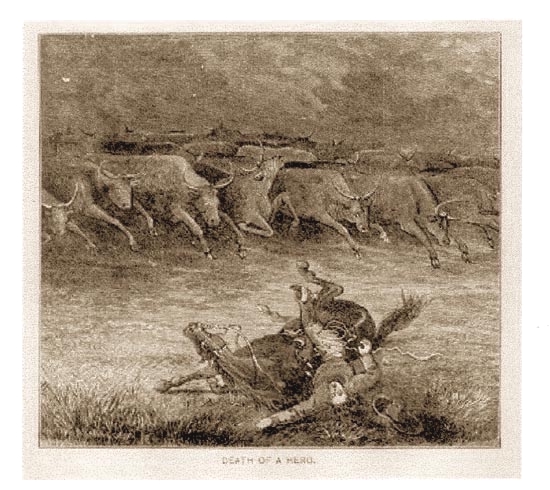

Death of a Cowboy on the Trail, woodcut, 1887

Stampedes would often be started by the night time thunderstorms of the plains.

Joseph G. McCoy in his 1874 Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the

West and Southwest explained:

Few occupations are more cheerful, lively and pleasant than that of the

cow-boy on a fine day or night; but when the storm comes, then is his

manhood and often his skill and bravery put to test. When the night is

inky dark and the lurid lightning flashes its zig-zag course athwart the

heavens, and the coarse thunder jars the earth, the winds moan fresh and

lively over the prairie, the electric balls dance from tip to tip of the

cattle's horns then the position of the cow-boy on duty is trying far more

than romantic.

When the storm breaks over his head, the least occurrence unusual, such as

the breaking of a dry weed or stick, or a sudden and near flash of

lightning, will start the herd, as if by magic, all at an instant, upon a

wild rush. and woe to the horse, or man, or camp that may be in their path

The only possible show for safety is to mount and ride with them until you

can get outside the stampeding column. It is customary to train cattle to

listen to the noise of the herder. who sings in a voice more sonorous than

musical a lullaby consisting of a few short monosyllables. A stranger to

the business of stock driving will scarce credit the statement that the

wildest herd will not run so long as they can hear distinctly the voice

of the herder above the din of the storm. But if by any mishap the herd

gets off on a real stampede. it is by bold, dashing, reckless riding in

the darkest of nights, and by adroit, skillful management that it is

checked and brought under control. The moment the herd is off, the cow-boy

turns his horse at full speed down the retreating column, and seeks to get

up beside the leaders, which he does not attempt to stop suddenly, for such

an effort would be futile, but turns them to the left or right hand, and

gradually curves them into a circle, the circumference of which is narrowed

down as fast as possible, until the whole herd is rushing wildly round and

round on as small a piece of ground as possible for them to occupy. Then

the cow-boy begins his lullaby note in a loud voice, which has a great

effect in quieting the herd. When all is still, and the herd well over its

scare, they are returned to their bed-ground, or held where stopped until

daylight.

The process of running the cattle back into themselves to end the stampede, was referred to as

"milling" the herd. The "electric balls" noted by McCoy were known to early cowboys as

"foxfire," possibly from phosphor. To sailors it was known as "St. Elmo's fire. It was sometimes seen in

conjunction with the coming of an electrical storm. At night in the rain often nothing could be seen except the

foxfire. John B. Kendrick came up the trail in 1879. He later recalled,

that "the only thing visible was the electricity on our horses' ears and the lightning

creeping or crawling along the ground at our very feet. More than once in my experience

I have seen cattle killed within 25 or 30 feet of me."

One instance near Ogallala was described by

early cowboy G. W. Mills:

The storm hit us about 12 o 'clock at night. There was some rain, and to the northwest I noticed just a few

little bats of lightning. Then it hit us in full fury and we were in the midst

of a wonderful electrical storm. We had the following varieties of lightning, all

playing close at hand, I tell you: It first commenced like flash lightning,

then came forked lightning, then chain lightning, followed by the peculiar blue

lightning. After that show it rapidly developed into ball lightning, which rolled

along the ground. After that spark lightning; then, most wonderful of all, it settled

down on us like a fog. The air smelled of burning sulphur; you could see it on the horns

of the cattle, the ears of our horses and the brim of our hats.

Joseph McCoy (1837-1915), a cattle broker, is general credited with initiating the

trailing of cattle from Texas north to railheads. He established the

stockyards in Abilene, Kansas. Within a few years after 1867, a company

with which he was associated was shipping as much as 1000 head a week.

An historic marker has been erected on E. Johnson Street, Denison,

Texas, in his memory.

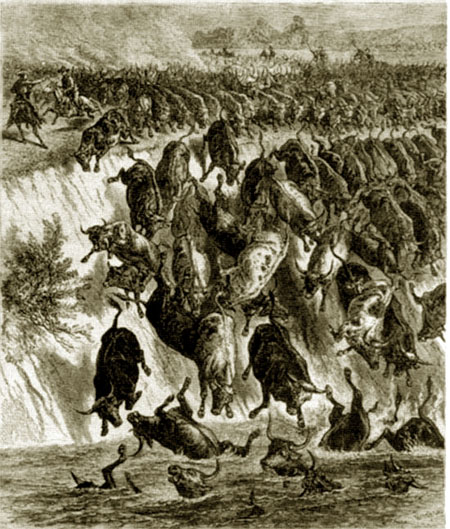

Stampede on the Pecos

As suggested by McCoy, the slightest thing might set off the stampede.

Frank Benton recalled a stampede set off by a tenderfoot named Curley striking a match on

his saddle horn:

When that match popped, there was a roar like an earthquake and the herd was gone in the

wink of an eyelid; just two minutes from the time Curley scratched his match, that

wild, crazy avalanche of cattle was running over that camp outfit, two and three deep. But at that

first roar, I was out of my bankets, running for my hoss and hollering, "Come on, boys." with a rising

inflection on "boys." The old hands knew what was coming and were on their hosses soon as I was,

but the tenderfeet stampeded their own hosses trying to get onto them,

and their hosses all got away except two, and when their riders finally got on them, they took across the

hills as fast as they could go out the way of that horded of oncoming wild-eyed demons.

The men who lost their hosses crawled under the front end of the big heavy roundup wagon, and for a wonder the herd didn't

overturn the wagon, although lots of them broke their horns on it and some broke their legs.

Cowboy Life on the Sidetrack, p. 102

"and for a wonder the herd didn't overturn the wagon."

Jacob

Bennett recalled a stampede from when he was riding for Tom Curry's TC, southeast of

present day Waco, Texas:

There was another stampede I saw while on the TC, and it was sort of a

freaky one. After a hard rain, the cattle'd all been standing up and it

looked like we were going to ride it out without them critters stomping,

but a fellow rode up on his hoss and got down to talk to another of the

boys that had built a small fire to make a little coffee. Well, he had

one of them fancy saddles with conchas all around it, and his saddle

rattled. An old steer snorted right loud; another took it up, and in

less time than it takes to tell it, the whole herd was on the stomp,

running just as hard as it could go with a deep draw right in front of

them about two miles away.

Well, you know a herd can run for 20 miles. Not likely to, but they've

been known to run that far, and lots farther. We knowed if the herd ever

reached this draw, they'd plunge on over and most of the herd would be

crushed to death, or kicked to death by those who fell in on top.

There was only one thing to do, and that was to out run the herd and mill

it.

[Writer's personal note: My grandfather, at about age 12, reversed

Horace Greeley's admonition and went East after being caught in a stampede

near Pueblo.]

Caught in a Stampede

William Owens, who had been orphaned at age 12 and went to work for the

Western Union Cattle Co., before moving on, described one stampede:

"I was with the Strayhorn outfit up in Arzonia. We had gathered 1,500

critters for market. The cattle were bunched and ready to start drifting

and we were intending to start the next morning at sun. About mid-night

a storm struck and lightening hit in the middle of the herd. As usual,

the animals were fretful before the storm hit. They did not bed and were

moving here and there. All hands were out trying to quiet and hold the

critters down. We were singing and whistling trying to give the critters

comfort, but they were all set to run just waiting for something that would

start the running. The sky-fire was what furnished the excuse and they went

off like a bunch of race hosses do when the gun is fired.

"At the jump we knew holding that herd was out of the question, so we just

tried to keep those critters from scattering until they tuckered out a bit.

Of course, it was dark and we could not see the herd or each other that

were riding, except when a flash of

sky-fire lit up the country. However, at all times we could hear the

clashing of horns and could tell about where the herd was. We waddies

kept each other posted on our location by firing several shots at a time.

The first shot was to draw attention and the other shots were given so the

fire flash could be seen.

"It was 10 miles to the Pareco River and we calculated on getting the

critters under control before the river was reached, but failed to do so.

We reached the river the critters were still going at a good rate

of speed and about half of the animals went into the water and four

of the waddies did likewise before they realized where they were going.

There was quick sand [and] sand bars at the point where the bunch run

into the river. Immediately there was plenty of scrambling and floundering

of men, cattle and hosses, in the dark and rain. No one could see enough

to do anything and we just had to wait for daylight. Of course, the

part of the herd that hit the water blocked to other critters and that

stopped the run. We put the land critters to milling, which were joined

by a few that got back out of the water and quicksand bog. When daylight

came we found two waddies, Sandy Peters and Arzonia Slim, drownded.

"Two of the waddies fished the drownded lads out while the others of us

went to work pulling out bogged critters, which were still alive. We worked

all day at pulling out bogged critters, but lost 300 which drownded.

"Pulling out Bogged Critters"

"The two waddies were buried on the banks of the Pareco River. We dug

the graves deep enough so that the wolves could not disturb the bodies.

I was selected to do the preaching and did the best I could. I requested

the Lord, 'to take them in, because their

hearts were pure as gold. While they were rough, tough and cussed, all

their acts were done with good intentions. They were true to their fellow

men, to their work and to every trust'."

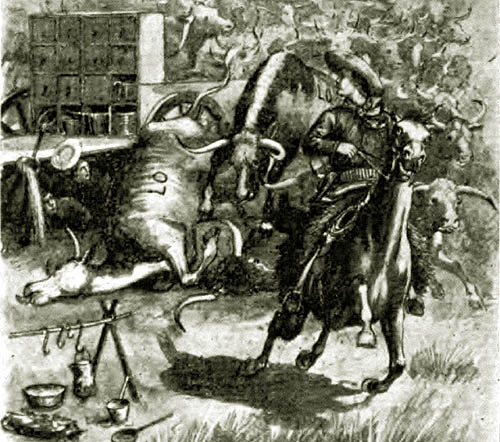

A Stampeded Herd, J. A. Castaigne, Scribner's Magazine

One method of stopping a stampede is to ride to the lead of the thundering herd and turn them into themselves, a process called '"milling."

It is frought with danger, illustrated in the next image exhbited by W. R. Leigh in the 1915

Panama-Pacific Exhibition.

"Stampede," painting by W. R. Leigh, 1915

To the right of the cowboy in the center of the above image, another cowboy's horse stumbles and the cowboy

is thrown head-first before the on-coming herd.

William R. Miller (1856-1955),studied art in Germany. Upon his return to the United States, he became an illustrator for

Scribner's and Collier's magazines. Between 1910 and 1913 he accompanied Cody taxidermist William "Will" C. Richard on three hunting trips into Yellowstone and along

both the North and South Forks of the Shoshone River which inspired his interest in Western art. Most of his

art was, however, centered on the American Southwest. Following World War I, Leight also painted scenes in

Kenya, the Belgian Congo and in Asia. On those trips he was also accompanied by Richard.

And once let the herd at its breath take fright,

And nothing on earth can stop its flight;

And woe to the rider, and woe to the steed,

That falls in front of its mad stampede!

Those oft repeated lines expressing the danger of a stampede are from Frank Desprez's "Lasca," about the death of

a cowboy's girl friend in a stampede.

Desprez worked as a cowboy in Texas for three years prior to 1875 prior to his return to his native

England. He rarely talked of his time in Texas.

Indeed, it is not known for what wagon he worked.

Lasca was first published in England in 1882 and subsequently in the Miles City Stockman.

The final verse of the poem:

And the little gray hawk hangs aloft in the air,

And the sly coyoté trots here and there,

And the black snake glides, and glitters and slides

Into a rift in a cotton-wood tree;

And the buzzard sails on—

And comes and is gone—

Stately and still like a ship at sea.

And I wonder why I do not care

For the things that are, like the things that were—

Does half my heart lie buried there

In Texas, down by the Rio Grande?

The death of a cowboy in a stampede is immortalized in the old cowboy song, "Little Joe, the

Wrangler." Background music:

LITTLE JOE, THE WRANGLER

Music by Will Harper

Lyrics N. Howard "Jack" Thorp

As sung by Marty Robbins

It's Little Joe, the wrangler, he'll wrangle nevermore;

His days with the remuda- they are o'er.

'Twas a year ago last Summer, he rode into our camp,

A little Texas stray and all alone.

It was late in the evening he rode up to our herd

On a little old Texas pony he called Chow;

With his brogan shoes and overalls, a tougher lookin' kid,

You never in your life had saw.

His saddle was a Texas kack built many years ago,

With an O.K. spur on one foot lightly swung;

His"hot roll" in a cotton sack was loosely tied behind,

And a canteen from the saddle horn was slung.

He said that he had to leave home, his paw married twice;

And his new ma beat him every day or two,

So he saddled up old Chow one night and lit a shuck this way

And he's now trying to paddle his own canoe.

He said if we would give him work, he'd do the best he could,

Though he didn't know straight up about a cow;

So the Boss he cut out a mount and kinder put him on,

For he sorta liked this little kid somehow.

Learned him to wrangle horses and to try to know them all,

To get them in at daylight if he could;

To follow the chuck-wagon and always hitch the team

And help the cocinero rustle wood.

We had driven to the Pecos, the weather being fine,

We had camped on the south side in a bend,

When a norther commenced blowin', we had doubled up our guard,

For it taken all of us to hold them in.

Little Joe, the wrangler, was called out with the rest,

Though the kid had scarcely reached the herd,

When the cattle they stampeded; like a hailstorm, long they fled,

And all of us were riding for the lead.

'Tween the streaks of lightnin' we could see that horse far out ahead-

T'was little Joe, the wrangler, in the lead;

He was ridin' "Old Blue Rocket" with his slicker o'er his head,

A-trying to check the cattle in their speed.

At last we got them milling and kinda quieted down,

And the extra guard back to the camp did go;

But one of them was missin', and we all knew at a glance

T'was our little Texas stray, poor Wrangler Joe.

Next morning just at daybreak, we found where Rocket fell,

Down in a washout twenty feet below;

And beneath the horse, mashed to a pulp, his spur had rung the knell

Was our little Texas stray, poor Wrangler Joe.

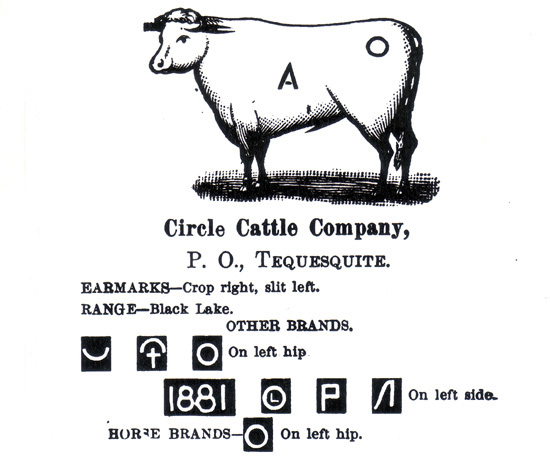

Thorp later indicated that the song was written on a paper bag while he was on a cattle drive of

"O" cattle from Chimney Lake New Mexico to Higgins, Texas. See "Banjos in the Cow Camps," Atlantic Monthly,

August, 1940. Higgins, at the time, was a shipping point

for cattle. It is somewhat subject to speculation, but the "O" may reference cattle owned by the

Circle Cattle Company. See below Thorp first sang the song to his

mess mates on the drive and later in a saloon in Weed, New Mexico. "Kack" used in the song

is a saddle, sometimes the reference was to a saddle with a small horn and double cinch.

Brands for "O" Cattle.

Next Page, Cattle drives continued.

|