| From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: the Dalton Trai Continued; Siria M. "Si" Dawson, Augustus G. Dawson and Manley M. Dawson; Skaquay; Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith; Leonard Sugden; and The Cremation of Sam McGee. |

|

| From Wyoming Tales and Trails This Page: the Dalton Trai Continued; Siria M. "Si" Dawson, Augustus G. Dawson and Manley M. Dawson; Skaquay; Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith; Leonard Sugden; and The Cremation of Sam McGee. |

|

|

|

|

About This Site |

Chilkoot Pass on Way to the Klonkike. Even though Bonnaza Creek had all been claimed, the Rush to the Klondike continued, fueled in part by the nationally reported story of a Rock Springs sheepherder Antone f. Stander (also spelled "Anton"). Stander emigrated to the United States at age twenty from southern Austria, later a part of Yugoslavia, and found employment at Rock Springs as a miner and sheepherder. By 1896 he had accumulated $400 and took off for the Klondike. By the time that he reached the Yukon, potential claims along Bonanza Creek had all been taken. He therefore explored what would later be called El Dorado Creek. By 1898, he returned to the United States, bearing an estimated 1200 lbs of nuggets, a millionaire. The story in the St. Paul Globe, Oct 23, 1898, p 8, described Stander:

Antone Stander at home on El Dorado Creek.

In 1908 Violet filed for divorce, obtained an injunction against his selling property. She was ultimately, according to the Dawson Daily News, Feb. 5, 1908, awarded $1,000,000 in alimony. Part of the award consisted of a half interest in The hotel. Violet and Stander could not agree on the operation or the sale of the from the celler to the roof. It went through rooms and closets. Violet's half included the dining room, and elevator. They still could not agree. Violet sold her half to the WMCA for $740,000 payable at the rate of $750.00 a month over 30 years without interest. Stander's interest was operated as the "Congress Hotel." Both Stander and Violet remarried. Violet's new husband alleged ran off to San Fransciso with $40,000 of her fortune. Stander remarried in British Columbia. Later census data reflects that he subsequently divorced. There is always another strike over the next hill. With his fortune gone, about 1919 Stander went to Siberia to search for gold. Upon his return, he claimed that he found deposits richer than the El Dorado claims. Unfortunately, the Bolsheviki seized his claim and he returned to Seattle broke. SeeDawson Daily News, Nov. 20, 1922. Stander' remaining interest in the hotel was sold. The new buyer sold the remaining half to the YMCA and the hotel was razed in 1930. A new YMCA building was constructed on its site. Stander made his way back north, allegedly securing his passage by peeling potatoes in the ship's galley. By 1930 and in 1940 he was residing in a bording house in Talkeena, Alaska, a small town on the Cook inlet near Anchorage. Pierre Benton, "Stampede for Gold, the Story of the Klondike Rush" Sterling Publishing Company 2007, contends that he died in the Pioneer Home in Sitka. On the other hand, Lee Morgan in "Good Time Girls of the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush, Sterling Publishing Company. contends that Stander was evicted from the Home as a result of drunkedness. What happened to Stander? On April 2, 1952, a minimal notice appeared in the Portland Oregonian :  Was it Antone Ferrell Stander, or was it another Antone Stander? If so, what was he doing in Portland? Another who went to Alaska and the Yukon was cowboy Angus McPhee (1874-1948) originally from Wyyoming. McPhee became a packer for the Quarter Master General in Alaska. After the Yukon he returned to Wyoming, rode in Buffalo Bill's Wild West and in 1908 became Champion of the World in the Cheyenne Frontier Days. That took him to Hawaii where he continued his career as a rodeo cowboy. In 1910, he lost one arm in an accident. Nevertheless, he continued. In 1915, with only one arm, he won the steer roping contest in the Hilo Rodeo beating his own time of 1:16 from the 1908 Honolulu Fourth of July contest. He became the manager of a ranch on Maui. It was not just miners, sheepherders and sheepherders who attempted to find fortune in the Klondike. One letter from an American soldier formerly stationed at Fort D. A. Russell was quoted in the Big Horn Rivr Pilot, November 3, 1897, as indicating that a large number of undesireable types were flocking to the area. The soldier noted that they had "large numbers not miners, but expect in some way to get a part of the money miners may have." One of those who came north to Alaska was Wyatt Earp. Earp in four years running the Dexter Saloon in Nome allegedly managed to mine about $80,000 out of the pockets of prospectors. The Dexter reputedly housed a bordello on the second floor. The soldier continued, "We have doctors, lawyers, speculators, state senators, thieves, cutthroats and politicians." Among the politicians was a former governor of Washington State, John McGraw, former Wyoming State Senator John N. Tisdale (see the Johnson County War, p 3, and the mayor of Seattle who resigned his office to head north. Among the lawyers and politicians was Melville C. Brown of Laramie who lobbied long and hard for a position as a judge in the judical system in Alaska. Two months before the letter from the soldier, a Deputy United States Marshal, William C. Watts had been murdered. The door to the courthouse in Sitka seemingly had a revolving door. One nominee by President Cleveland was a defrocked Methodist Minister. Five judges were appointed within twelve years. It has been speculated that the judgeship was a way of getting Brown out of Wyoming. See Viner, Kim: "Alaska Gets a Wyoming Judge", Annals of Wyoming "Autumn 2014. P 2. Indeed, to a great extent, Judge Brown may have been the burr under Judge Carey and Senator Warren's saddles. Senator Warren wrote Judge Carey, "Personally, I would rather crawl on my hand and knees in the gutter a block in Cheyenne, that to see even the worst of our three democratic judges replaced by Brown." See Viner, supra. Judge Carey had been involved in bitter litigation with Edward Ivvinson an outgrowth of which was Brown denouncing the Supreme Court as having been bribed. See In re Brown, 3 Wyo 122 (1884) in which the Court suspended Brown from the Bar for have called the court a "Son of bitch of a court, -- one bribed and the other I don't known what." Brown served out his four years term, but after an investigation of complaints about Brown, President Roosevelt requested his resignation. See San Francisco Call, November 17, 1904. Brown returned to Seattle, practiced law there and ultimately returned to Laramie. The Mizner Brothers were to the son of a former American Ambassador to the Central American States Lansing Bond Mizner. Wilson and Addison were noted for alleged cheating of the Roman Catholic Churches in Central America of priceless artifacts and art which Addison later peddled on Fifth Avenue for large sums. In the Yukon, Wilson secured employment as a piano player and "Gold Weigher." When measuring the quantity of gold dust, he managed to spill some of the dust on the floor. At the end of the week, he would mine the carpet for the dust. As a piano player, he allegedly inspired Robert W. Service's "The shooting of Dan McGrew." The center piece of the poem was a piano playing contest between a stranger and the saloon's professional piano player. Allegedly, Service was inspired by a challenge by Wilson to the piano player in the Dominion Saloon (or maybe it was the Monte Carlo Saloon) called the Rag-Time Kid." The Kid claimed that he could play anything requested. Wilson sat down and played the "Holy City" and challenged the Kid to play the same tune, the background music for this page. The Kid bested Wilson.  Dawson, 1898, Monte Carlo Saloon. Further down the street the Dominion Saloon is under construction.

By Robert W. Service 1874–1958

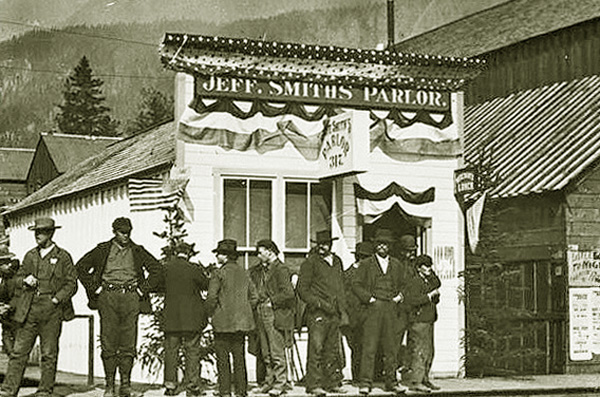

Jeff's Parlor, Skaquay, Alaska, 1898. Trail. The town of Skagway at this period of its existence was about the roughest place in the world. The population increased every day; gambling hells, dance halls and variety theatres were in full swing. "Soapy" Smith, a " bad man," and his gang of about 150 ruffians, ran the town and did what they pleased; almost the only persons safe from them were the members of our force. Robbery and murder were daily occurrences ; many people came there with money, and next morning had not enough to get a meal, having been robbed or cheated out of their last cent. Shots were exchanged on the streets in broad daylight, and enraged Klondykers pursued the scoundrels of Soapy Smith's gang to get even with them. At night the crash of bands, shouts of " Murder! " cries for help mingled with the cracked voices of the singers in the variety halls; and the wily" box rushers " (variety actresses) cheated the tenderfeet and unwary travellers, inducing them to stand treat, twenty-five per cent, of the cost of which went into their pockets. In tin- dance hall the girl with the straw-coloured hair tripped the light fantastic at a (dollar a set, and in the White Pass above the town the shell game expert plied his trade, and occasionally some poor fellow was found lying lifeless on his sled where he had sat down to rest, the powder marks cm his back and his pockets inside out.One Deputy United States Marshal was murdered when answering the complaint by a Andy McGrath, a British subject, that he had been scammed in the bar of the People's Threatre, a combination saloon and bordello. Both the marshal and Andy were shot and killed by the bartender. The next deputy marshal was in the employ of Smith. Things boiled over later in the year when a prospector was robbed of almost $3,000 worth of gold (1898 dollars). Complaints to the federal government had gone unanswered. Some of the business people tired of the criminal element gathered at the Juneau Wharf to decide what was to be done. Smith and some of his minions tried to force their way in. In an incident later known as the "shootout at the Juneau wharf," Shots rang out. The City engineer was shot by Smith. Simultaneous shots believed to have come from the Engineer found their mark in Smith who died instantly.It has also been contended that Smith was shot by someone else. Since it would not have been self-defense, it would have been murder. But Jeff Smith probably deserved. Therefore it was convenient to pin Smith's death on the City Engineer. The City Engineer lingered from his wounds and finally died when infection set in. The remnants of Smith's Gang including the currupt deputy United States marshal decided that Skaquay was no longer healthy. Canton was hired by the United State Marshal to serve along the American portion of the Yukon. He was fired several months later upon instructions of the Attorney General and never drew a paycheck.

Soapy Smith, 1898.

Officers of Division B, Northwest Mounted Police, Dawson City, 1900.

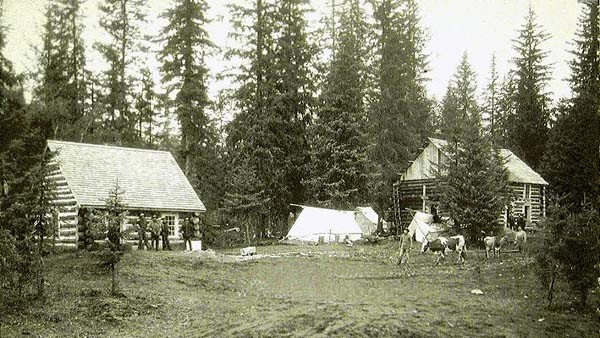

Northwest Mounted Police station on the Dalton Trail.

Toll Tent, Dalton Trail.

Dalton Trail.

Some drovers would drive the cattle to Dawson City down the ice on the Yukon River. This may have avoided the perils of the rapids or being stuck on sand bars but added an additional peril of the ice breaking up underneath the herd. In 1903, newlyweds Grace and Chris Bartsch trailed 500 sheep, 50 cattle and one goat to Dawson City and barely escaped the ice breakup. From the shore, they watched in horror as others went into the icy, raging waters. The Bartsch animals had to be transported the remainder of the distance on a scow. The last cattle drive on the Dalton Trail was in 1906.

Prospectors' Scow. "You Americans are hard men to kill. Coming down the river I -met over three hundred men on their way out, and most of-them were from the States and knew nothing of the cold that is cold, or how to take care of themselves right. Yet they acted as if they were on a picnic, and as if the devil were really dead. They didn't seem to mind little inconveniences like frozen feet and cheeks, and hands with the nails coming off and blistered with the frost. They're reckless devils, and a more cheeky set I never met. With the pants burnt off their l egs and the faces on them like brown parchment from the fire and frost, they had the gall to give me advice about the country, to tell me how many pairs of moccasins I'd need for the trip, and the like, when I was born on a snow drift and got my growth under the midnight sun. You Americans would storm Hades if you thought the heat had melted out any gold down there; and you'd put up so good a bluff and are so nervy, I'll be bound you'd get some of the stuff if there was any there." Even if using a scow or barge to carry the cattle was risky. Before reaching Lake LeBerge, one came to Miles Canyon and the White Horse Rapids. Burnham described passing the remains of a boat on its side. It had gone through the rapids sideways, hit an obstruction, turned over and the crew and cargo swept over and carried down through the canyon. Burnham wrote, "there is little doubt but that its crew perished." Burnham continued that "rude notices on the east bank warned us to land." If one survived the frost bite, but provisions ran low one might starve. Burnham recalled, At Fort Selkirk, "four hundred miles from food and safety" starving prospectors "tantalized by the sight of rafts l aden with beef and mutton for the Dawson market, aground and abandoned on bars in midchannel, a feast for the ravens." On a trip to the coast, he "saw some ravens tearing at an object which on closer inspection proved to be the ribs and upper portion of a man's body. There were many gruesome associations on that journey in the dead of the Sub-Arctic winter. Tottering out of the blue-grey haze of snow and frost-laden spruces, came from time to time starving men, almost as emaciated as the plague victims in India, with the light of an insane fear in their eyes, whom bitter experience had taught that it was better to risk death by stealing food rather than to risk refusal by begging for it. At Fort Selkirk, two half-crazed men came into Burnham's cabin and "without a word seized upon a loaf of bread and some prunes, which was all the prepared food in sight, and began eating ravenously, like beasts that expected to be driven away. When they had finished they left without asking for more or saying a word of thanks for what they had taken. The men had black spots on their cheeks, where the flesh was frozen into the bone and would never grow again." Prospectors were ravaged by scurvy. Indeed, Jack London suffered himself suffered from that malady. We tend to mishear some of Johnny Horton's lyrics in his "When it's Springtime in Alaska," the actual words in the final verse are not "When springtime in Alaska, it's 60 below" but, "he'll be six feet below." Scurvy was a hazard of cod liver oil in a little shot glass. In the evening having nothing to do with scurvy, one might find putrified shark in a jar with a lid on it to keep down the aroma. Scurvy is indirectly responsbible for one of the Yukon's most famous poems by Robert W. Service suggested from one of the adventures of Dr. Leonard Sugden, a surgeon with the Royal Northwest Mounted Police. Dr. Sugden was one of those explorers that the British public school system tended to produce at the end of the 19th Century. He served as post surgeon in Hong Kong, received from the emperor of China the title of Mandarin of the Second Class and served in the Boer War. In the Yukon, he acquired an early motion picture camera and achieved some fame filming conditions there. In 1916, Dr. Sugden joined Owen Rowe O'Neil's expedition into the darkest part of Swaziland. There, he visited the Swazi school for witch doctors. He caught dysentary but on the point of dying was cured by a native witch doctor by the muti a magic leaf grown from a secret location known only to the head witch doctor. Normally muti is reserved only for royalty. Sugden was conferred the native name MLung Emantzi Eenuiinduna in the swazi Impi. Following his return from Swaziland, Dr. Sugden spent time exploring parts of Brazil. In 1922, he disappeared from a steamer on the Stewart River near Mayo, British Columbia. it is unclear whether he was murdered or whether he accidently fell in. His body was never recovered.

Dr. Sugden on right, following his induction into the Impi, Swaziland, 1916.

The Steamer Olive May, Upper Yukon River.

Richard W. Service

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

Now Sam McGee was from Tennessee, where the cotton blooms and blows.

On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson trail.

And that very night, as we lay packed tight in our robes beneath the snow, "

Well, he seemed so low that I couldn't say no; then he says with a sort of moan:

A pal's last need is a thing to heed, so I swore I would not fail;

There wasn't a breath in that land of death, and I hurried, horror-driven,

Now a promise made is a debt unpaid, and the trail has its own stern code.

And every day that quiet clay seemed to heavy and heavier grow;

Till I came to the marge of Lake Lebarge, and a derelict there lay;

Some planks I tore from the cabin floor, and I lit the boiler fire;

Then I made a hike, for I didn't like to hear him sizzle so;

I do not know how long in the snow I wrestled with grisly fear;

And there sat Sam, looking cool and calm, in the heart of the furnace roar;

There are strange things done in the midnight sun

By the men who moil for gold;

Next Page, The Edmonton Trail, Byron F. Wickwire.

|