Hanna Railway Depot, 1910.

Hanna Three was located south of the Lincoln Highway, several miles to the east of Hanna One and Two. Elmo was an open town in contrast to

Hanna which was a company town. In a company town everything belonged to the company, the houses, the commercial buildings and the company store.

Although a company town had advantages to the coal company. It permitted almost total contraol over the employees. Employees lived in company houses. If they lost employment,

that were summarily evicted and they were cut off at the Company store. Thus, Tennessee Ernie Ford sang,

Sixteen tons and what do you get, another day older and deeper in debt, St. Peter don't call me, I owe my soul to the Company Store."

Union Pacific Coal Company Store, Hanna, undated.

Company stores were, however, not all bad.

The use of scrip was a form of cash

advance, permitting a newly employed miner to have the necessities of life, while awaiting his first paycheck and assurred

the miner's family that the paycheck would not be squandered at the saloon. company houses precluded a major loss to the miners if

the mines closed. Later in Hanna after the town was opened to ownership of the houses by the residents, many lost their life's

savings when the mines closed in the 1980's. Houses sold for one-third of their original

purchase prices.

Employees Union Pacific Coal Company Store, Hanna, undated.

Above and to the left, Locomotive No. 58 at Hanna Tipple, 1939.

Locomotive No. 58 was used in Cecil B. DeMille's epic movie "Union Pacific."

Locomotive No. 58 was used in Cecil B. DeMille's epic movie "Union Pacific."

On June 30, 1903, the worst mining disaster in the history

of Wyoming occurred in Mine No. 1. As previously noted, the area had originally been called "Chimney Spring as a result of

a fire in one of the coal beds. In Mine No. 1, the oldest of the Hanna mines, there had been long lingering fires, but they were isolated behind alleged

air-tight bulkheads. On June 30, 1903, at 10:25 a.m., a tremendous explosion rocked the mine. There were 234 men within the mine. The force of the

explosion hurled heavy support timbers out of the mine 1,700 feet into town. One timber struck the power house some 200 yards away going through

the steel reinforced walls. Within the mine there were 234 men. Of those 169 were killed. Most were on the 17th level where it is thought that the

explosion occurred. four miners survived, led out by a Black miner, Will Christian. On the same level, five mules and one horse escaped going to the same shaft as used

by Christian. One miner committed suicide thinking there was no

hope. Within the mine were five

"fire bosses" making a safety inspection. All were killed. Six hundred children

were rendered fatherless. The Finnish community had the largest toll losing some 100 men. the New York Independent, May 7, 1903, in reporting the explosion commented on the

Finns:

The people in the Wyoming coal mines are mostly men without a country; some of them Poles,

more of them Finns. The Finns are hard working and honest, and their children in the public

schools outstrip the other nationalities, including native American.

The most prominent building in the town is the Hall of the Finnish Temperance Society.

It must not be thought that temperance here means total abstinence, as it usually does with us.

In fact, what to a Finn is temperance would in some cases seem to other people immoderation;

but the hall serves as a center of the social and religious life of the community and keeps

alive something of the national spirit.

* * * *

Not many months ago a singular mail arrived in Hanna. Usually, of course, the foreign mail

brings its ordinary mixture of good and bad news, and the recipients are glad at least to hear

from home: but this mail saddened every Finnish heart before it was opened, and strong, rough

men broke into tears at the sight of the envelopes. The postmaster could not understand how

they knew that the letters contained bad news before they read them, but the Finns pointed to

the stamp. It was the Russian stamp and they knew their country was no more. It was the death

of the fatherland.

Writer's note

Prior to 1899, Finland was a Grand Duchy of which the Russian Czar was the Grand Duke represented by

a governor general. Under Alexander II, it had been given much

autonomy in its affairs including its own parliament, use of its own language, postage stamps, and church.

In 1899, Nicholas II began a program of "Russiafication" of Finland requiring the use of Russian postage stamp, Russian

lanquage in the administration of the country, the Russian Orthodox Church became the State Church. It was briefly eased from

1905 to 1907 but reinstituted. World War I and the Russian Revolution provided the opportunity for Independence. The Russian

stamp on the evelopes indicated the death of autonomy for the country. Alexander II is honored in Finland. A statue of the

"good Czar" remains in the main square of

Helsinki.

Statue of Alexander II, Helkinki, photo by William Henry Jackson, 1905.

Hundreds of blankets and mattress arrived from Laramie and Rawlins. Two hundred suits were ordered from Denver by the

Coal Company for used on the bodies of the dead. It turned out that there was no need for the

mattresses and blankets. Two hundred twenty-five caskets arrived from

Denver and Rawlins and were stacked against the south wall of the Finnish Temperance Hall awaiting use as the bodies were removed over the following

month. In the backyard of the hotel,

pine crosses were painted white, The crosses and the caskets served as mute reminders of the tragedy to

passengers on the passing trains.

Subsequently the mine was reopened. Tp prevent accidental ignition of coal dust from the use of explosives, miners were instructed that frozen dynamite

should be thawed using manure rather than using lanterns. Photographs

depicted the possible consequences of violation of the rule. Of course every cowboy knows that horse manure generates heat.

The snow always melts first over the manure pile next to the horse barn.

On March 28, 1908 there were two more explosions in Mine No. 1. On Sunday March 22 at 1:00 a.m.,

one of the fire bosses discovered a fire. In a subseqeuent report to

Governor B. B. Brooks, a state inspector indicated that the fire was probably caused by a shot, but he noted:

"The true cause of the fire will probably never be known as no witnesses are now left." On the 28th, at about 3:00 p.m. Company Superintendent Scotsman

Alexander Briggs with the foremen of Mines 1, 2, and 3 along with a select experienced team of

miners was fighting the fire, an explosion rocked the mine. Several one foot in diameter timbers were blown against the

tipple 300 to 400 feet from the mouth of the mine. Another timber was blown 400 to 500 feet falling near the boiler plant. There were no survivors.

Tipple and boiler plant, Hanna Mine No. 1, after partial clean up, 1908.

Edith Erickson later

recalled that at her house, six men, all relatives and friends, were playing dominoes. Upon the sound of the explosion the men quickly left to

see what happened, telling her to leave the dominoes and draughts so they could finish the game when they returned.

She continued, "So thats what I did. But they stayed so long I got the next meal ready for all of them, and waited and waited."

Caved in mouth of west slope, looking toward the tipple,, after partial clean up, 1908.

A state safety inspector David M. Elias was on the west-bound Number 3 train at the time of the explosion. He was notified

by telegraph of the explosion and immediately headed to Hanna and arrived at about an hour after the explosion.

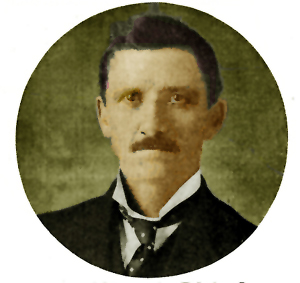

David M. Elias, State Safety Inspector David M. Elias, State Safety Inspector

At about

5:30 p.m., Inspector Elias took charge of the situation as all persons with authority had been killed in the 3:00 o'clock explosion or

overcome by poisonous fumes. Inspector

Elias with a party of ten entered the mine. He left a man behind with strict instrucions that no one else should be permitted in the mine.

Not withstanding the instructions about fifty men entered the mine apparently in an effort to assist in the rescue of anyone

left alive within it. At 10:15 another explosion occurred. Mrs. Erickson continued:

"The next morning was Sunday. I put the game away and the dishes of food

I had cooked. You see, it was up to me to do these things.I didn't have a relative nearer than England.

I was all alone, if you understand what that is."

Eighteen were killed in the first explosion, forty-one in the second explosion. Two and a half months later one body was

recovered. And on July 17 thirteen more bodies were recovered. The mine was then sealed. The bodies of all but one of

Superintendent Brigg's party were never recovered. All of the six who left Mrs. Erickson's house were killed. Each widow received $800.00 and each surviving child under the

age of fifteen, $50.00. Widows who wished to return to Finland were provided transportation.

They were not the

first mining disasters in the state, nor the last, just the worst. Earlier,

disasters had occured at in 1886 at the Almy No. 4 Mine with 13 killed; in

1895 at Red Canyon near Evanston with 60 killed. In 1901, at Diamondville, two disasters occured, one

on Feb. 15 with 26 killed, and another on Oct. 26, with 22 killed. Later disasters occured

in Kemmerer No. 4 mine in 1912 with 6 killed;

Cumberland No. 2 Mine with 5 killed; the Frontier No. 1 Mine near Kemmerer in 1923 with

99 killed; and Sublet No. 5 Mine in 1924 with 39 killed. Nor were they the last miners to die in the mines in the

Hanna Mines.

Initially most of the miners in Hanna came from the British Isles and as indicated above from Finland. Later miners came from

other countries including Greece and Japan. In 1914 five miners were killed in the No. 2 mine from falling coal: Y. Nomasa, who left a widow and three children;

R. Kido; Dominic Simonain who left a widow and five children; Oscar Werten; and Anton Slelik. In 1921, four were killed in the

No. 4 mine: James Whie who left a widow and seven children; Jack Spenser, a teamster killed by being kicked by a horse;

Pete Xirakis killed by falling rock; and Michael "Mike" Mamanakis (1883-1921) killed by falling coal while loading a pit car. He left

a widow and six children one of whom was not quite a year old. Mike and his wife had come from Vamos, Crete. His widow and family moved to

Helper, Utah, where she operated a boarding house for miners.

Next Page: The Mines 2 and 4.

|