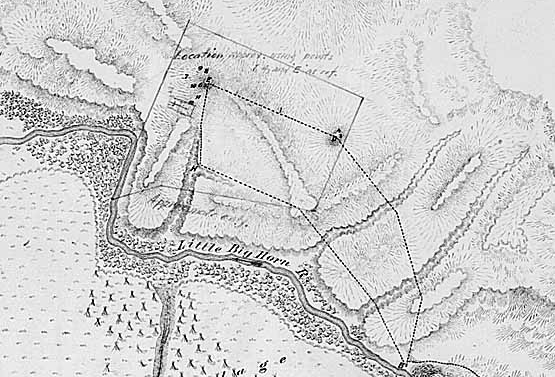

Portion of Maguire Map (see previous page), depicting Last Stand Hill.

On the afternoon of the 25th, Grouard, dressed as a Sioux, rode north. That night he found the trail left by Custer's forces and soon came across the

body of a dead soldier. From a Sioux he learned of the battle, but the Sioux soon

suspected he was not of them. He was, thus, pursued by four Sioux for more than fifty miles before

eluding the pursuers.

On the 26th, in accordance with Terry's plan, Gibbon was cautiously moving his way toward the scene. Warned by scouts of

Gibbon's approach, the village was dismantled and the Indians disappeared into the

Bighorns. The next day the extent of Custer's defeat was learned. Lt. George Wallace described moving to the

scene of Custer's fight, "but the sight was too horrible to describe. We buried 204 bodies and encamped near Gen'l Terry. But

the smell of dead horses forced him to move camp several miles." Bodies were down by the river, and another

smaller group, as shown by the numbers on the above map, were found below the crest of what is now known as

"Last Stand Hill." There were found the bodies of (3) Custer's brother-in-law, Lt. James Calhoun; (4) Lt. J. J.

Crittenden; (5) Lt. Col. Geo. A. Custer; (6) Custer's bother, Capt. T. W. Custer; (7) Capt. G. W. Yates; (8) Lt. A. N. Smith;

(9) Lt. W. Reilly; (10) Lt. W. W. Cooke; (11) Custer's bother, W. B. Custer; and

(12) Custer's nephew, Armstrong Reed. Some distance to the southeast were found (1) the body of Capt. (Brevet Lt. Col.) Myles Walter Keogh.

Near Keogh's body were found the bodies of his two sergeants, bugler, and

flag bearer.

Among those killed at Little Bighorn was Custer's dog Tuck. In his letter of June 12 to Libby

Custer, Custer wrote:

"Tuck" regularly comes when I am writing, and lays her head on the desk, rooting up

my hand with her long nose until I consent to stop and notice her. She and

Swift, Lady and Kaiser sleep in my tent.

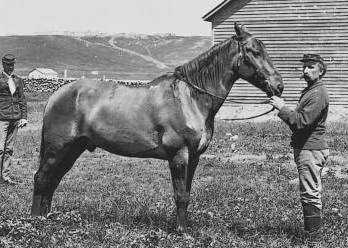

Comanche held by Gustave Korn as unidentified officer looks on. Photo by F. Jay Haynes.

Comanche held by Gustave Korn as unidentified officer looks on. Photo by F. Jay Haynes.

At the Battle of the

Little Bighorn, Korn (1852-1890), referred to by his fellow soldiers as "Yankee," was Capt. Keogh's orderly and was

assigned to the Custer column but was saved from the

fate of the rest of Custer's men when his horse bolted when the troop reached the

river. The horse had taken the bit in his mouth and carried Korn through the

Indian lines to Reno and Benteen's units on what is now known as "Reno Hill."

Henry P. Jones, also assigned to Keogh's Company I, later recalled:

When the packs were ascending the "Hill" we saw Korn coming towards us very much

excited, his horse foaming at the mouth. Sergt. Delacey [sic], who was

in charge of I Troop's packs asked him how it was he left the troops; he

said his horse ran away with him. His case was investigated and [he] was

exonerated afterwards. He was on the hill the 25th and 26th and proved

himself to be no coward, having brought water a great many times. Korn was killed at the Battle of Wounded Knee in

December 1890.

Although, Korn participated in the dash to the water, he was not among those

granted a Medal of Honor. Not all of Keogh's men participated in the Custer battle. Keogh's Company I packs

were left behind with Sergeant Milton J. De Lacy. Thus, Company I men assigned to the

packs such as De Lacy and Jones survived. The only survivor found at the

Custer Battlefield was Comanche, Capt. Keogh's horse. Comanche suffered

from multiple wounds and a loss of blood. He was evacuated with Reno's wounded to

Fort Abraham Lincoln. Most sources, based on biographies of Capt. Grant, indicate that Comanche was evacuated with

the other wounded on board the Far West. Thus, as an example, Joseph M. Hanson in

The Conquest of the Missouri, 1946, describes Captain Marsh making a place for the

horse "softly bedded with grass" at the stern between the rudders. Nevertheless,

the Chicago Times, August 20, 1876, reported that Comanche was evacuated on the

sternwheel steam packet E. H. Durfee. At Fort Lincoln Comanche was nursed back to

health. General Sturgis directed that he never again be ridden. Comanche was placed under the care of Korn and would

be occasionally brought out for parades. Following Korn's

death, the horse seemed to lose interest in life and died in November 1891.

He was stuffed and placed in a museum at Lawrence, Kansas.

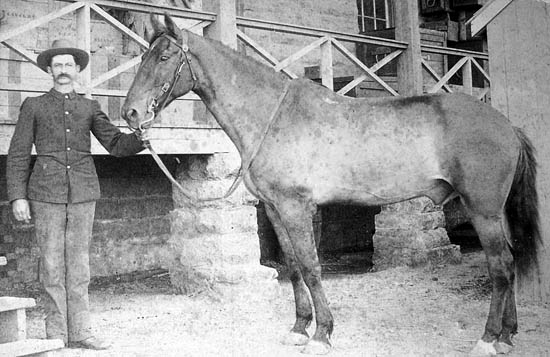

Comanche

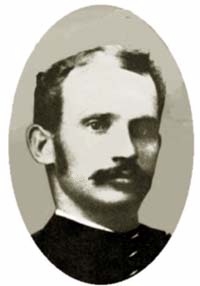

Keogh was born in County Carlow, Ireland and served as an officer in the army of

the Pope during the Wars of Italian Unification. He emigrated to the United States in

1861 and enlisted in the Union Army seeing service in the Valley of Virginia and

at Gettysburg.

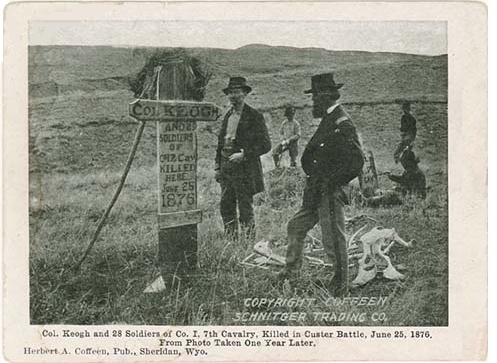

Wooden marker for Myles Keogh, 1877, photo by Stanley J. Morrow.

As noted above, the only living survivor found on the battlefield was

Comanche. Over the years, rumors have abounded as to the existence of survivors from Custer's Last

Stand other than Korn, Martini, Kanipe, Comanche, and the Indian Scouts. The Scouts, of course, never

claimed to have been in the battle. They were excused in advance. Horses were captured by the

Sioux. Following the battle, horses that had not been shot were rounded up by the Indians. Thus,

as an example, stories have been circulated that Custer's own horse "Vic," ("Victory"), was

captured and was later in the possession of Walks-Under-the-Ground.

Amongst the Arikara Indians, there is the legend of Little Soldier, a horse belonging to one

of Reno's Arikara scouts, Bobtailed Bull, killed in the battle. Little Soldier, according to the

legend, bedraggled and still bearing his saddle, found his way 300 miles to his home village in

Dakota Territory from Little Bighorn.

Custer with Bloody Knife (pointing to map), 1874.

Other rumors relate to the survival of two dogs. In addition to Tuck who travelled with Custer on his

last journey, Custer took with him a number of greyhounds. The greyhounds were left with packers

at the previous night's encampment and, thus, survived. It has been contended that Tuck

was not left behind and may be

regarded as one of the casualties of the battle. Several observations of a dog on the battlefield were made.

It has also been contended that Tuck stayed with Custer's dog handler, Private John Burkman at the

pack train. No accounts following the battle have been found of Tuck's fate.

Of humans, the three most

controversial accounts of survivors are those relating to Frank Finkel,

Charles Hopkins, and Company L's (Calhoun's) farrier, William Heath.

Frank Finkel

In 1920 at a Rotary Club meeting, a claim was made by Frank Finkel of Dayton, Washington State,

that he had served with Custer at Little Bighorn. Allegedly, Finkel had run away from home in

Ohio and in 1874 enlisted in the Army under the name "Frank Hall." He contended that

he used the fictitious name since he was underage. During the battle,

a bullet struck the butt of his gun which splintered, sending a splinter of wood

into his forehead. At the same time a bullet hit his horse in the flank. The horse

bolted and carried Finkel through the Indian lines. Finkel was hit twice by

bullets, one in a foot and the other in his abdomen. After reaching some hills, Finkel went into hiding.

He made a tourniquet from a blanket in an effort to stop his bleeding. After hiding for

four days, he found a cabin with two occupants, one named Bill, the

other, later identified to Hinkel only by his initials "G. W.," was terminally ill in bed. Finkel was still bleeding. G. W.

from his death bed gave instructions to staunch the wound with hot pitch. When G. W.

expired, Finkel helped bury him and carved G. W.'s initials on a stone grave

marker. Bill gave Finkel directions fron the cabin to civilization. Finkel set out

and caught a steamboat to Fort Benton. At Fort Benton, Finkel read in a newspaper that Custer and

all of his men had been killed. He proceeded to St. Louis and from there moved west to

Washington State.

The account, based on its details and the refusal of Finkel to change portions to fit

known facts, was apparently regarded by Custer historian Charles Kuhlman as making the

tale more credible. The difficulty with the account is that there was no record of either a "Frank Finkel" or a

"Frank Hall" in the Seventh Cavalry. In this regard, Hinkel should not be confused with

either Curtis Hall or Edward Hall in Weir's Company D, both of whom survived.

Additionally, census records reflect that

Finkle was born in Ohio in 1854 and was, thus, not underage. It has, therefore, been suggested that Finkel may have

forgotten the name under which he enlisted or that Finkel was really George

August Finkel, a sergeant in Thomas Custer's Company C. That contention, however, does not wash in

that George Finkel was not from Ohio but from Prussia. Frank Finkel was also

adamant that he was a private and occasionally an acting corporal, but never a

sergeant. Sgt. Finkel's body was additionally one of those actually identified. It can, however,

be argued that the identification was in error. Further, Frank Finkel was insistant that he

rode a roan horse. Company C used sorrels. Each Company had different colored horses. Custer in

My life on the Plains, Chapter 9, explained:

After everything in the way of reorganization and refitting which might be

considered as actually necessary had been ordered another step, bordering

on the ornamental perhaps although in itself useful, was taken. This was

what is termed in the cavalry "coloring the horses," which does not imply,

as might be inferred from the expression, that we actually changed the color

of our horses, but merely classified or arranged them throughout the

different squadrons and troops according to the color. Hitherto the horses

had been distributed to the various companies of the regiment indiscriminately,

regardless of color, so that in each company and squadron horses were found of

every color. For uniformity of appearance it was decided to devote one afternoon to

a general exchange of horses.

The troop commanders were assembled at headquarters and allowed, in the

order of their rank, to select the color they preferred. This being done,

every public horse in the command was led out and placed in line: the grays

collected at one point, the bays, of which there was a great preponderance

in numbers, at another, the blacks at another, the sorrels by themselves;

then the chestnuts, the blacks, the browns; and last of all came what were

jocularly designated the "brindles," being the odds and ends so far as

colors were concerned-roans and other mixed colors-the junior troop

commander, of course, becoming the reluctant recipient of these last,

valuable enough except as to color.

Charles Windolph

Charles Windolph

To some extent Finkel has also lost credibility by his declination to

meet with the last known surviving member of Reno's and Benteen's Companies,

Charles Windolph (1851-1950) of Benteen's Company H, who might otherwise

have been able to confirm or refute his claims. It also must be said that the

steamboat trip to Fort Benton in the opposite direction from Fort Lincoln has to strain the credulity of

even the most naive. Finkel was married in Washington State in 1886, but during the

entire time thereafter until 1920 never mentioned his association with Custer, apparently,

not even to his wife. Thus, for the

reasons indicated above, Finkel's claims remain unproven and are generally

not accepted.

[Writer's comment: As noted, Finkel's first known statement as to

being at Little Bighorn was at the Rotary Club meeting. At the meeting there was a speaker on the

Battle of Little Bighorn. Finkel challanged the speaker as to some point. The speaker

asked Finkel as to his souce of information. Finkel responded by the statement that

he was there. It may be speculated that Finkel's account was a little lie which grew.]

Windolph for his actions at Little Bighorn received a battlefield promotion

to Sergeant and received a Medal of Honor as one of the

four marksmen who covered the dash to water. He came to

the United States in 1870, speaking scarcely twelve words of English, to avoid the draft in his

native Germany during the Franco-Prussian War.

Three Chiefs, photo by Edward S. Curtis

Three Chiefs, photo by Edward S. Curtis

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) is regarded as the foremost documenter of Native Americans. During the

period 1907-1930, he published some 2,000 photogravures of Native Americans.

Charles A. Hopkins

Similar to the claims of Frank Finkel, are the claims by Frank T. Hopkins, a New York City

subway tunnel worker, relating to his father

Charlie Hopkins. According to Frank Hopkins his father served as a scout for Custer, guiding Custer to the Little Bighorn. There, Custer and

the elder Hopkins got into an argument over Custer's disregard of orders to await the

arrival of Terry. The elder Hopkins was then taken prisoner by Chief Gall who inquired after

"Miles Kellogg" and expressed regret at the necessity of Kellogg's death. Thus,

Hopkins sat out the battle. Thereafter, Charles Hopkins was carried as a prisoner by the

Sioux to the Canadian Northwest. He returned home to Fort Laramie

some four months later. The family ranch in Wyoming is identified variously as being south of Ft. Laramie, south of Laramie,

near Sundance, and near

Cody.

Needless to say, Frank Hopkins' claims are suspect. There is no record of

a Charles Hopkins at Little Bighorn. The younger Hopkins is subject to considerable controvery. He claimed to

have been born in 1865 in a log cabin south of the parade grounds at Fort

Laramie; to be a long distance endurance rider having ridden from Galveston to Rutland, Vermont in 1886,

and, at the behest of Nate Salsbury, from Aden along the "Gulf of Syria" 3,000 miles to an unidentified location north of

Arabia. [Writer's note: The "Gulf of Syria" was the location of "Antekirtta," a secret island in a Jules

Verne novel about a master-hypnotist avenging a Transylvanian nobleman who had

been wrongfully imprisoned.] Additionally, Hopkins claimed he performed from 1886 to 1906 as a headliner in Col. Cody's Wild West.

He claimed he had

a personal audience with Queen Victoria, was a friend of Col. Roosevelt, guided Zane Grey to the bottom of

the Grand Canyon, and grew up

on the family ranch near Ft. Laramie speaking no English until age seven. He claimed that his mother

was the daughter of Geronimo and that he believed that Chief Joseph was Geronimo's brother. His descriptions of Fort Laramie, where he allegedly

grew up, appear to be inaccurate. In his description of his father returning to

Ft. Laramie following Little Bighorn, Hopkins seemingly has an image of a

palisaded fort. This is confirmed by his description of an alleged return to the

fort years later. In his account, Hopkins indicates that the fort was in "Big Horn country" and that all

that remained at the time of his visit were a "few posts visible above the ground * * * * What was once the old

Bozeman Trail is now cut upon into roads leading into the Town called Laramie." [The Big Horns are some 200 miles

from Ft. Laramie. Laramie is about 100 miles from Ft. Laramie.]

Investigation by the American Heritage Center in Laramie has been unable to

support any of Hopkins' claims. The Cody Museum has found no records in support of Hopkins having

worked with the Wild West Show. The writer has been unable to find any records relating to his

purported birth at Fort Laramie in 1865. There was a Frank Hopkins born in Fort Laramie. However, it was

Frank Everett Hopkins born in 1895 and who died in Washington State, not Long Island. Hopkins is not found in either the

1870 or 1880 Census for Laramie County. A Charles Hopkins was found in the 1880 Census for

Albany County. Unfortunately, his middle initial was "H" and he was one month old. A Frank Hopkins whose father was named Charles was found in

in the 1880 Census for Big Sioux, Dakota Territory. Charles was a farmer and Frank was eight months old. Frank's

mother was born in New Hampshire. No record of a land patent for the

family ranch in Wyoming has been found in favor of Charles A. Hopkins. In a news release the American Heritage Center's

Associate Director Rick Ewig referred to Hopkins' claims as a "tissue of lies." He noted that if

Hopkins' claim that he rode dispatch from Ft. Laramie to Ft. Kearney were believed, Hopkins would have

been three years old at the time.

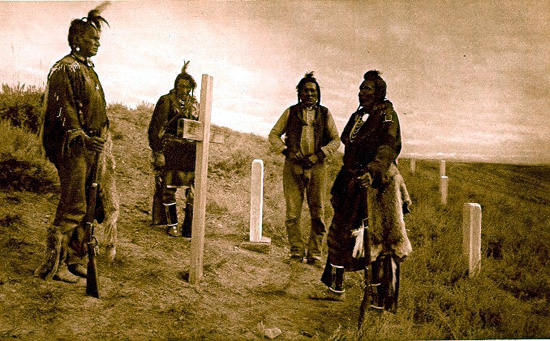

Custer's scouts at site of Custer's death. L to R:

Goes Ahead, Harry Moccasin, Curley, and White-Man-Runs-Him

The above photo has been attributed to various photographers and has been dated as

1890, 1906, and 1913.

William Heath

According to amateur historian Vincent J. Genovese in

Billy Heath: The Man Who Survived Custer's Last Stand, Prometheus Books,

William Heath, originally from England, settled at an early age in Girardville, Schuylkill County

Pennsylvania. There he married, but because of death threats departed town, leaving wife Margaret and son

John behind. In October 1875, Heath enlisted in

the Army in Cincinnati, Ohio, and was assigned to the Seventh Cavalry at Fort Abraham Lincoln as a

farrior. He allegedly survived the carnage, wandered about the countryside towards the

Bozeman Trail, and was found by the Ennis family who nursed him back to health. He then returned to his

family in Girardville. There, he resumed work as a coal miner Out of graditude Heath named his

daughter Levina after Mrs. Ennis. Heath lived out his life in Girardville and nearby Tamaqua until he

died in 1891, never having spoken of his adventures or applied for an

Army pension. He was buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery. It is contended that

the story is confirmed by family oral tradition and the disappearance of Heath from the Tax Rolls during the

mid-1870's.

Like many family traditions, the story has difficulties. The William Heath who

enlisted in the Army in October 1875 indicated that he was age 27, single, and had worked as

a coachman. The 1880 Census (five years later) for Girardville indicates that the Girardville William Heath was

age 28 and was, thus, four years younger than the one who enlisted at

Cincinnati. The age of the Girardville Heath is also confirmed by the

1890 Census for Tamaqua. The Girardville Heath was married on September 21, 1872, and had

seven children including a second son, William, who, according to the 1880 Census, was born in 1876. One source, however,

indicates that the son was born on November 5, 1875. The

1890 Census shows the son to be age 13. If the census information is to be

believed, it is highly unlikely that the

William Heath who was in the Army could have been the father of the son of the Girardville William Heath.

On the other hand, if the

son were born in 1875, the Girardville Heath, under the Genovese scenerio, left child and pregnant wife behind to

enlist in the Army, lied about his age and marital status, learned the

farrior's trade in only two months, and then deserted following Little Bighorn.

Thus, the Girardville Heath does not match Company L's farrior in the following aspects:

(1.) Age. The Girardville Heath was four years younger than the age given for the

Company L's Heath;

(2.) Occupational training. The Girardville Heath was a coal miner. Company L's Heath was a coachman and

farrior;

(3.) Marital status. The Girardville Heath was married and at the time of Little Bighorn had one and possibly

two children. Company L's Heath was single; and finally

(4.) The timing of the birth of the son is possibly inconsistent with the father being away in the Army or

wandering about in Wyoming or Dakota Territory.

[Writer's observation: In doing historical research it is very easy to add several coincidences of

name and dates together and arrive an an erroneous conclusion as to the

identity of individuals. The writer has, himself, ridden down many trails based

on identical names, only to discover that the person being traced was not the

person being researched.]

It must be noted that well known Custer historian E. A. Brininstool (1870-1957), Troopers with Custer and

A Trooper with Custer, tracked more than 70 claims of

survivorship. All were for naught. Nevertheless, Brininstool, himself, recognized the

intriguing possibility that there was a survivor. In May, 1921, General Godfrey wrote Brininstool of the discovery in

late July or the first of August, 1876, of

a horse on the south side of the Yellowstone near the mouth of the Rosebud::

"I heard a rumor that [some infantry troops] had found a dead horse that was fully

equipped, except bridle, and that it was a Seventh Cavalry horse. I went to the steamer at once

to investigate. I crossed to the south bank of the stream and found the horse. It was impossible

to determineif it was a sorrel or light bay animal. Halter, lariat, saddle, saddle-blanket and

saddle bags were intact; and strapped to the cantle was the small grain bag with which the

Seventh Cavalry and provided itself. The oats in the bag had not been disturbed. The saddle bags

were empty. I was told that when first discovered the carbine of the rider was there. The horse had been shot in the

forehead, which must have been fatal on the spot."

Gen. Godfrey continued by noting that as he was examining the animal, the sound of the boat's whistle summoned him back and he was

not able to continue the examination until the next day. When he returned, the equipment had been removed. The horse was so

baddly decomposed that its brands could not be identified. Godfrey was unable to learn anything

further of the horse or who its rider may have been.

In commenting on Godrey's letter, Brininstool noted that all officers with Custer had been

accounted for but Lieutenants Harrington, Porter and Sturges whose bodies were never found. Brininstool asked,

"Who rode the solitary animal found dead by Captain Godfrey a few weeks after the

Custer fight, on the lonely banks of the Yellowstone river, which carried Seventh Cavalry equipments? Was its rider one of

Custer's men, and who was he?" Brininstool, E.A: "Was there a Custer Survivor?" Hunter-Trader-Trapper magazine, April 1922.

There was, however, another provable survivor, a gray horse taken to Canada by the

Sioux and recovered by Northwest Mounted Police superintendent James Morrow Walsh.

The horse, being gray, would have belonged to Lt. Algernon E. Smith's E Company. Walsh

wrote General Terry asking if he could keep the horse. Superintendent Walsh ultimately received a response from

the Adjutant General, E. D. (Edward Davis) Townsend that the Secretary of War had authorized

Walsh to retain the horse. Walsh renamed the horse "Custer." It seems to be one of the

few times that Townsend delivered pleasant news. He is the one who relayed the

orders of President Hayes dismissing Reno from the service and those of President Lincoln

relieving McClellan from command.

Next page: Battle of the Little Big Horn continued.

|