|

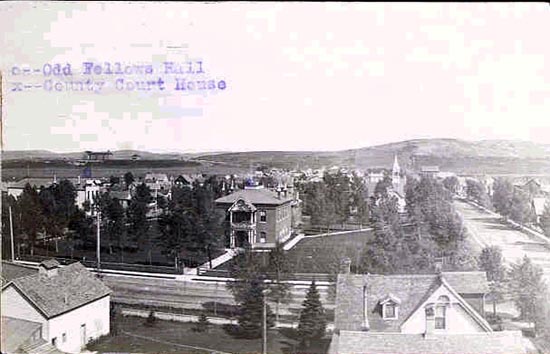

Uinta County Courthouse, undated.

The first structure in Evanston, built by Harvey Booth (1840-1895), was a

saloon and restaurant located in a tent on what is now Front Street. Within a month the town

had a population of approximately 650. Later Booth operated a hotel at 9th and Front Street.

The Railroad

reached Evanston in December of 1868. Shortly thereafter Evanston was designated as the county

seat.

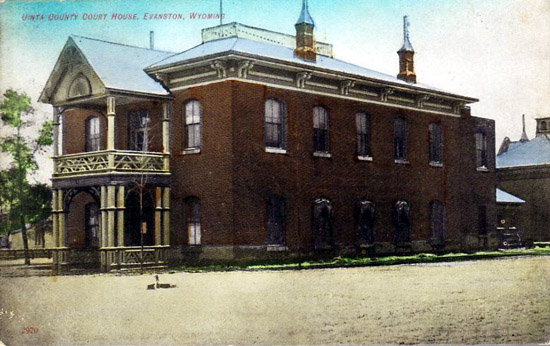

Uinta County Courthouse, undated.

The Court House was built by Harvey Booth for $15,425. In contrast, in 1907, the Federal

Court House and Post Office was built with the assistance of an appropriation obtained by

U.S. Senator, C.D. Clark from Evanston, in the amount of $184,000.

Federal Courthouse, Evanston, 1910

Booth was appointed as Sheriff in 1870 and served until the general election of 1872. In the

mid-1870's, Booth became a partner with with Edwin S. Crocker, Wm. Crawford, and Wm. Thompson in a

meat market. Gradually the meat market became a major cattle operation and the four were among the wealthiest ranchmen in the

state. On January 26, 1893, Crawford disappeared in a blizzard on his way to a Masonic dance in the Peter Down's Opera House.

Crawford was a bachelor. Two days later his team was discovered in a private barn unfed and unwatered where he had left them

while it was to be at the dance. It was only then

that it was realized that he had vanished. A major search was made for him but to no avail. Periodically, rumors that he had been sighted were heard and

checked out, but they always were for naught. Thompson brought an action to foreclose on cattle owned by

Crawford. Other creditors, however, brought an action in the Distict Court to enjoin the foreclosure sale and to have

a receiver appointed for Crawford's property. Ultimately on April 19, 1894, Crawford's property was sold by the

receiver at public action. Thompson purchased most of the assets.

It was a common belief that Crawford was murdered. He was, however, not legally declared dead until 1905 after his mother died in

Illinois and it became necessary to have Crawford declared dead in order to close out her estate.

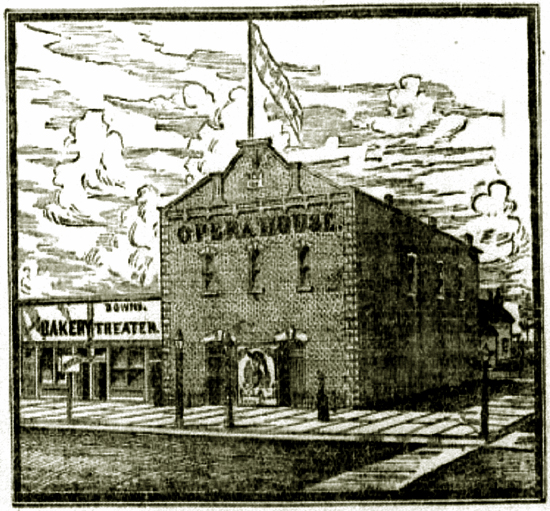

Opera House, 1892

The Opera House was constructed by Peter J. Downs in 1885 and cost some $12,000. The basement featured a skating rink.

The advertising curtain depicted A. B. Beckwith's barn

On the evening of January 26, 1895, two years to the day following the disappearance of Crawford,

there was a theatrical troupe was appearing at the Opera House. Among those

planning on attendance that night were former sheriff and Mrs. Harvey Booth and Mr. and Mrs. Edwin S. Crocker. Also planning to

attend was Dr. Winslow who was scheduled to act as an usher. Booth and Crocker remained partners in a

cattle ranch outside of town. In addition to the ranch, in townn, Booth and Crocker jointly owned a barn at the

corner of Tenth and Main Streets where later would be constructed the

Federal Building. Each also had comfortable houses.

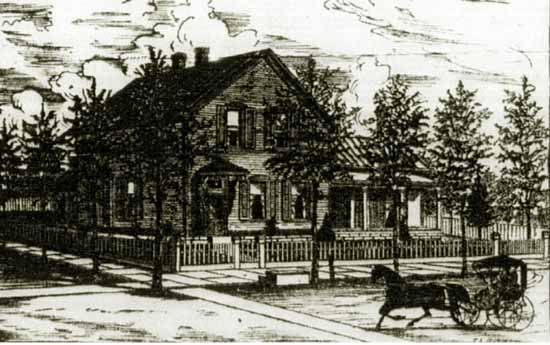

Residence of Edwin S. Crocker, circa 1895

Each of the partners used a separate part of the barn. A milk cow owned by Booth was also kept in the

barn. Sometime between 5:00 and 5:45, Booth left Hocker and Solomon's drugstore. He noted that he had to

tend to somethings at the barn. At about 4:30, a delivery of hay for Booth had been made at the barn. Crocker was

passing by and showed the hay man where to place the hay. The two partners also shared an office about a block from the Barn. Crocker's house was located two blocks from the

barn. At twilight, At twilight, two girls, 14 year-old Effie Walton and a friend Pearl Butterworth were sledding down the hill in fron of the barn.

Both recognized Harvey Booth and saw him entering the barn. A civil engineer testified that the sun set at

precisely five hours, thirty-three minutes and three seconds after 12:00 noon astonomical time. Effie saw through the open door a man with a white face and a "funny nose" hit

Mr. Booth with a club or baseball bat. The man was wearing gray clothes. Effie could not identify the man. Effie went home and had supper. At about 6:15,

John Parkinson entered the barn to milk Booth's cow. He observed nothing untoward.

10th Street, Evanston, Wyoming, approx. 1908.

Harvey Booth failed to return home either for supper in time to take Mrs. Booth to the Opera House. She bcame concerned and

canvassed the town looking for her husband. At 11:00 p.m. when Harvey still failed to appear,

Mrs. Booth asked a friend of her housekeeper to help look for Booth. They went to the barn. There they failed to observe anything

out of place except a slat loosened over a boarded uu window of the harness or bunk room. The room was

apparently locked. Therefore,

the friend peered through a hole in a boarded up window. There he

observed a prostrate form on the floor. The two went to Crocker's house and

told him they they wanted him to come with them to the barn as something was wrong. Crocker got

a lantern and directly led the way to the area of the barn where the body had been observed and crawled

through the window. The body's head had been covered with a gunny sack and over the gunny sack was a lap robe.

Sheriff Ward was sent for. Even before the sack and the lap robe could be romoved for identification of the body,

Crocker told Sheriff Ward that it was a clear case of robbery. Drag marks in frozen blood indicated that

Harvey's body had been dragged into the apparently

locked harness room. The temperature had fallen below zero that night. Harvey's ppockets had been inverted. According to Crocker, there was missing a certificate of

deposit and other papers. A twenty dollar gold piece that Harvey had been carrying was found on

the floor. An examination by a physician revealed that the cause of death was a blow by a blunt

instrument. John C. Hamm, the prosecuting attorney described Harvey's head as a "shapeless mass." Booth's

brains, according to Hamm, had been beaten "to a jelly." Sheriff Ward did not buy Crocker's arguments that it was

a robbery. As later stated by Prosecutor Hamm;

"When the man is murdered for the purpose of gain, his slayer usually contents

hmself with killing his victim, and then proceeding with robbery. But when

Harvey Booth was killed, his body was dragged some distance away,

his head covered with a gunny sack, and his brains beaten out, hatred and malice

and revenge are clearly shown."

Suspicion slowly focused on Crocker. Thomas Blyth employed the Pinkerton Agency to

investigate the murder of his brother-in-law and to assist in the trial. Blyth guaranteed the Pinkertons

fees of $8.00 per day for each agent assigned to the case. Apparently based on the work of the Pinkerton agents,

on February 8, 1905, the Cheyenne Daily Sun

accused Crocker of killing Crawford two years before and killing Booth. The motive, according to the

Sun was:

Harvey Booth possessed information of the killing of William Crawford by Crocker, and the latter knew that the terrible secret of his

partner's disappearnce was held by Booth. This caused a coldness between them. Since that murder the two men, although associated together in the

cattle business scarcely spoke to each other. A go-between was necessary, and for the past two years they have not been upon civil terms.

This fact was well known to othr cattlemen, but the cause thereof was not suspected.

Harvey Booth was made away with as a matter of self protection.

Crocker dare not longer trust him with the knowledge of the crime.

Crocker sued E. A. Slack, editor of the Sund for $25,000 for defamation. Based on circumstantial

evidence, Ed Crocker was indicted for the murder. The case attracted nation-wide attention and was reported in newspapers as far away

as Hawaii. A county commissioner was found in contempt of court for

attempting to contact jurors. At the trial, Crocker was found guilty. At that point,

Dr. Winslow appeared with new evidence: Crocker had an alibi: Crocker was at the Hotel Marx from 5:00 until 6:00 p.m. He was then at home until 7:00. After 7:00 p.m.

he was with Dr. Winslow's father from 7:00 p.m. or Dr. Winslow at the Opera House until information was received there of

Booth's murder. A new trial was granted and venue was transferred to Laramie County at the opposite end of

the state.

In Cheyenne, one of the leading trial lawyers of the day, Walter Stoll, was employed to lead the

prosecution on the second trial. Stoll later was to successfully try Tom Horn for the murder of Willie Nickell. At the second trial, Stoll relied on circumstantial evidence to indicate

Crocker's guilt. The time of death was established as between 5:00 or 5:30 p.m. when witnesses saw Booth leaving Hocker & Solomon's drug store and 6:15 p.m.

when Parkinson entered the barn to milk the cow.

Witnesses were presented who testified that there had been an increasing strain between Booth and Crocker over the previous five years.

Other witnesses testified that Crocker frequently wore a dark gray double breasted coat and had worn the suit the day of the murder.

Witnesses testified that after the murder they never saw the suit worn again.

Evidence was adduced as to an ash pile in Crocker's yard in which were found bits of metal and paper that looked like a check.

Testimony was presented that Crocker had been in the

Blyth & Fargo store twice, the first time at about 4:30 when he purchased an orange. After leaving Blyth & Fargo, Crocker testified that

he proceeded home, passing the barn and observed that hay was being delivered.

Booth. After instructing the hay man where the hay was to be placed. Crocker then proceeded home and worked on fixing the furnace. At about

5:30 he returned to the Blyth and Fargo store and purchased onions for his wife. From 6:00 to 7:00 p.m. he was at the Marx Hotel and thereafter

at the Opera House. Austin Sloan testified that

Crocker had told him that he Crocker had been at the barn between 5:30 and 6:00.

Marx Hotel and Restuarant, undated.

The Hotel Marx was operated by Thomas Bird, son of Jospeh Bird, Sr., owner of

the Hotel Evanston depicted on a subsequent page.

Walter Stoll was

unable to shake Dr. Winslow's testimony. Dr. Winslow's stuck to his guns and repeated his version of the alibi over and over again.

Crocker was with Winslow or with Winslow's father from 7:00 p.m. until

the doorman interrupted the performance to tell Winslow that Booth had been murdered. [Writer's comment:

Walter Stoll apparently fell into a trap by placing undue emphasis the cross-examination of Dr. Winslow. If the murder

occurred before 6:15, Dr. Winslow's testimony was essentially irrelevant. An additional question may be asked:

Why was the door to the harness room locked. If it were a robbery, why would a robber in fleeing the scene, take the

time to lock the door on the way out?] The Defense also presented testimony that

Crocker had only two suits, the dark gray suit worn in the winter and a light gray suit worn in the summer. The dark gray suit was pproduced and

identified by several witness as the suit

that Crocker had worn the day of the murder. Witnesses were provided that although there had been a strain between the two

partners, the partnership was very profitable and that the death of Booth had a serious impact on the

partnership's finances. A witness was presented who testified that there had been an outlaw

named Sullivan in the area. Sullivan had a big nose and

possibly matched the description of the man who was seen hitting Booth. Crocker testified that

Booth frequently carried a large sum of money with him which was missing. It was suggested that there was an outlaw in

the area named Sullivan with an ugly looking nose, who may have done the deed.

After three hours of deliveration, Crocker was found not guilty.

The murder remains unsolved to this day. Although Blyth paid the Pinkerton's for their successful efforts at the first trial, he

refused payment of their fees of $685.25 for their unsucessful efforts at the second trial. The Pinkerton's sued for their fees, but,

after an appeal, were unsuccessful in collecting their fees from Blyth. They then sued Sheriff

Ward and were ultimately awarded $900.00. One of Crocker's attorneys, Samuel T. Corn sued Crocker for money owed. Following the

not guilty verdrict. Crocker sold his properties in Wyoming and moved to Ogden Utah. From Ogden,

Crocker moved to Portland, Oregon. There, Mrs. Crocker operated with the Crocker's son-in-law and daughter, a lodging house.

It is believed that Crocker died in Portland prior to 1910. The lawsuit against

E. A. Slack was dismissed. The Booth and Crocker Barn was razed in 1904 to make way for the Federal

Courthouse. Thompson lost his fortune and died in Salt Lake City a pauper.

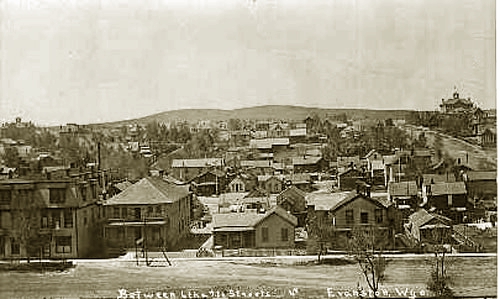

Evanston, between 6th and 7th Streets, 1906

Next page: Evanston continued.

|