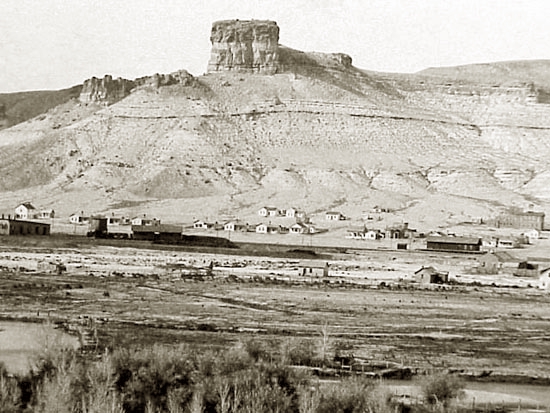

Green River City, 1880's, photo by C. R. Savage

For discussion of C. R. Savage, see Sherman.

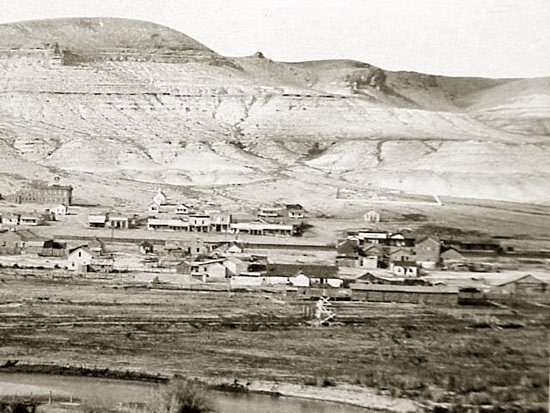

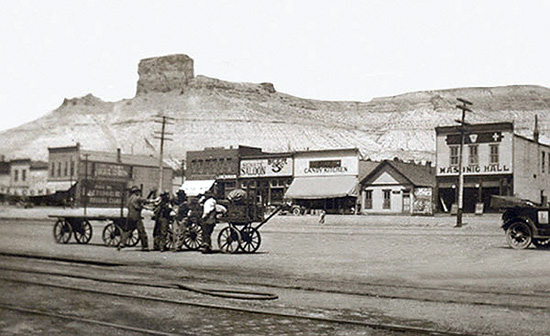

Green River, approx. 1927

Note the Masonic Hall. Today, it is common to refer to a Masonic lodge building as

a Masonic temple. At one point the writer referred to the hall in Meeteetse as the

"Masonic temple." He was promptly corrected. At the turn of the century in smaller towns, it was common for the

building owned by a fraternal order to be used as a community center often simply referred to

as the "Hall," in which dances, covered dish suppers and

other activities would be conducted. Elinore Pruitt Stewart in her 1914 Letters of a Woman Homesteader noted

that all towns in Wyoming had a "hall." To the hall, settlers would travel miles for a covered dish

supper and all-night dance. Children would be put to sleep under coats on benches on the walls of the

hall while the adults danced the night away. In Pinedale, as an example, when the Woodmen of the World constructed its

new hall, a dance was held not withstanding that the hall had no heat and it was five degrees

below zero. Music was generally by one or two volunteers on a fiddle, banjo, or guitar. Typically, the

repertoire might be small, but it did not distract from the festivies. Indeed,

Governor William Ross wrote of attending a dance at the Burntfork Odd Fellows hall. The governor noted that the dance was one

of his most enjoyable occasions. Gov. Ross recalled that the floor would bounce in time to the feet of the dancers. This caused doors

downstairs to bang in time to the music.

Burntfork Odd Fellows Hall, 1920's

Burntfork is about 50 miles southwest of Green River. When Mrs. Stewart arrived in Burntfork in 1909, a one-way trip to

Green River took two days. Mrs. Stewart's daughter, Jerrine Rupert Wire remembered:

My Wild Irish Rose", the sweet haunting melody floats to my ears and memory

swiftly flies back across the years. in fancy I see again the rough

two-storied building built of rough-hewn logs hauled from the near by

mountains. It is night and cold as all nights are in this high country.

The yard around the building Is filled with saddle horses and teams hitched

to light wagons and buggies. From the building pours the sound of music, gay and loud and beautiful to the ears of the listeners. Warm yellow light from the kerosene lanterns in the "hall" cut bright slices in the darkness. Inside the families of the ranchers in the remote valley are dressed in their very prettiest and are happily dancing, awkwardly, with much stomping and scraping and whirling. Dancing to old tunes almost forgotten now.

The fiddlers are neighbors who just "picked up" music and who play only a

limited number of tunes they all know. The good smell of strong coffee and

good cakes, of soap and water and perfume, of tobacco and liquor, and of

children, and sagebrush and pine. The great stoves at each end of the hall

roar merrily. Little children sleep on quilts and coats on the floor and

benches back of the stoves. Older children scamper about or try to learn

to dance.

Suddenly there comes the sharp sound of a man banging a stick on the floor of the dance hall. A laugh and knowing look passes quickly along the faces of the crowd. Everyone knows Mick, the lovely Irishman, the village drunk, a bachelor, a very fine smith and mechanic. His frail looking body is in reality a steel wire capable of enduring roughest, hardest labor and bitter cold. His beautiful blue eyes gaze over the crowd as his fogged wits collect themselves. Suddenly he stands proud and tall and poised and waiting. The fiddlers begin his song and from him comes the purest tenor voice singing lovingly, sweetly, "My Wild Irish Rose". The haunting melody lifts the souls of all who hear it from the dull days, the loneliness the disappointments, the ugliness of today's chores. Their minds soar with the rising notes and trip happily to the lilt of this simple song. They share again the love expressed by the young lover of long ago.

Mick's weaknesses and faults are gone and he who was never to know real

love, stands strong and filled with love and beloved. No one ever broke

the spell he cast upon all of us.

Stewart House, Burntfork

The Stewart house has continued to go to rack and ruin, inhabited only by

animals. The chimney is now collapsed, leaving a gaping hole in the

second floor where the fireplace used to be. Parts of the roof drape from the

cross beams and the yard where the garden used to be in strewn with rocks and timbers from the

house.

|

Elinore Pruitt Stewart

It is commonly reported that Elinore Pruitt Stewart was born in Fort Smith,

Arkansas. The 1920 Census for Burntfork indicates that she was born in Oklahoma.

Other information indicates that the place of birth would be in present day Caddo County, Okla.

At some point she was

married to Harry C. Rupert of Roger Mills County, Oklahoma. With Rupert she had a

daughter, Jerrine, born 1907. About 1908, Elinore, claiming to be a widow, arrived in Denver with Jerrine. She

obtained employment with Juliet Coney as a laundress and nurse. She was also involved with the Living Waters Mission, later known as the

Sunshine Rescue Mission, on Laramer Street. In 1909, pursuant to an advertisement, she took

employment with Clyde Stewart, apparently sight unseen.

Henry Clyde Stewart, according to the 1920 Census for Burntfork and the 1880 Census for

Boulder County, Colorado, was born in Pennsylvania [other records indicate Mercer County]. He and his wife

Cynthia arrived in Burntfork in 1898. The two had been married in Boulder in

1895. Clyde was widowed in 1907. Because of a reference in one of Elinore's letters

to Stewart retiring to his room to play The Campbells are Coming on the bagpipes, it is widely reported that he

was Scottish. She wrote in her first letter:

I have a very, very comfortable situation and Mr. Stewart is absolutely no trouble,

for as soon as he has his meals he retires to his room and plays

on his bagpipe, only he calls it his "bugpeep." It is "The Campbells

are Coming," without variations, at intervals all day long and from

seven till eleven at night. Sometimes I wish they would make haste

and get here."

The detail in the letter including the Scottish burr must be regarded as an artistic

license.

The trip to Burntfork took two days on the train, followed by two days on the

stage. Due to the quality of the letters, Mrs. Coney brought the letters to the

attention of Ellery Sedgwick publisher of the Atlantic Monthly. There they were

serialized and later published as a book. Within a short time, Elinore applied for

homestead on land immediately adjacent to Stewart's. At almost the identical time, Harry Rupert was

proving up his claim to homestead in Oklahoma. Harry later remarried. Almost immediately following the filing,

and within six weeks following her arrival in Burntfork, Elinore and Stewart were married and

Elinore's claim of homestead was assigned to Stewart's mother, Ruth C. Stewart.

The elder Mrs. Stewart proved up the claim in

1915. Elinore

neglected, however, to tell Mrs. Coney of the marriage for about 11 months.

In a 1915 letter, she wrote of her enjoyment of mowing:

The draft has made us so short of men that I find myself in my element

again, on the mowing machine. Oh, I'm glad I can mow and rake and even

stack hay. I have been having a perfectly lovely time helping. And we

have had a perfectly glorious fall. There has been no snow or rain and

the frost has been so light that my flowers are not harmed. My beautiful

blue and gold Wyoming! You would love it!

In 1926, Mrs. Stewart was mowing hay. Her horses bolted and she was run over by the

mower. She never fully recovered from her injuries and died in 1933. Clyde died in Montana but his body was

returned to the Burntfork Cemetery where he is interred next to Cynthia,

Elinore and infant son James Wilbur who died two days following Christmas

1910. The

grave is marked by the doorstone from the old house. Today, the garden is gone. The old log house sits forlorn, the roof and chimney

in partial collapse, home only to animals.

|

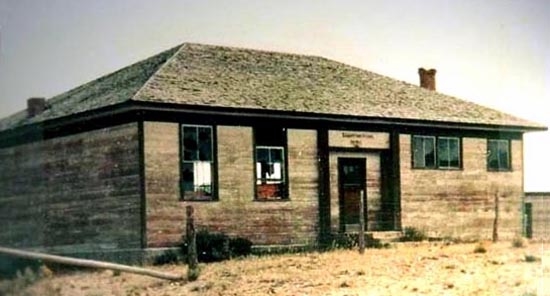

Burntfork School, 1920's.

Jerrine Rupert taught in the school. Her

step-father, H. Clyde Stewart, was for a period of time a trustee for the school. Both the

Odd Fellows hall and the school are gone now. The county clerk has recommended to the Board of County

Commissioners that the Burntfork voting precinct be abolished. In the 2004 election, Burntfork had only 14 voters.

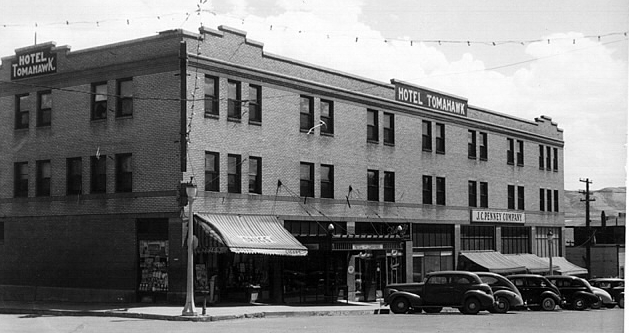

The next photo of the Tomahawk hotel is somewhat of a reminder of the relationship between

Green River and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. The hotel was allegedly named by combining

the first name of

Thomas Adderson Welch (1867-1963) and the last name of Dr. J. W. Hawk who paid for the hotel when they came

into a mysterious supply of money. Supposedly, Welch participated in the

Tipton train robbery and Dr. Hawk periodically treated gunshot wounds for members of the Wild Bunch.

Tomahawk Hotel, approx. 1940

Music this Page:

MY WILD IRISH ROSE

Music and Lyrics

By

Chauncey Olcott

If you'll listen, I'll sing you a sweet little song,

Of a flower that's now drooped and dead,

Yet dearer to me, yes, than all of its mates,

Tho' each holds aloft its proud head.

'Twas given to me by a girl that I know,

Since we've met, faith, I've known no repose,

She is dearer by far than the world's brightest star,

And I call her my wild Irish Rose.

My wild Irish Rose,

The sweetest flow'r that grows,

You may search ev'rywhere,

But none can compare

With my wild Irish Rose.

My wild Irish Rose,

The dearest flow'r that grows,

And some day for my sake,

She may let me take

The bloom from my wild Irish Rose.

They may sing of their roses which, by other names,

Would smell just as sweetly, they say,

But I know that my Rose would never consent

To have that sweet name taken away.

Her glances are shy when e'er I pass by

The bower, where my true love grows;

And my one wish has been that some day I may win

The heart of my wild Irish Rose.

My wild Irish Rose,

The sweetest flow'r that grows,

You may search ev'rywhere,

But none can compare

With my wild Irish Rose.

My wild Irish Rose,

The dearest flow'r that grows,

And some day for my sake,

She may let me take

The bloom from my wild Irish Rose.

Next page Green River continued.

|