|

Rock in the Glen. Photo by Geoff Dobson.

Register Cliff was not the only place that early travellers left their names. Just to the west of Deer Creek, present day Glenrock, is

the Rock in the Glen. There again, names of those making the trek westward were inscribed on the rock. Most of the

names are on the back side of the rock. Access, across a prickly pear strewn field, is by a foot path from a small park.

Directly in front the rock is a private residence.

Independence Rock

Names were also inscribed further to the west on Independence Rock, named by William Sublette in 1830, when his

freight wagons reached the rock on the Fourth of July. Over 5000 names are placed

on the rock. Even by 1842, the Rock was noted for the numbers of names left. Fremont

commented:

AUGUST. 1st.--The hunters went ahead this morning, as buffalo appeared

tolerably abundant, and I was desirous to secure a small stock of

provisions; and we moved about seven mules up the valley, and encamped

one mile below Rock Independence. This is an isolated granite rock,

about six hundred and fifty yards long, and forty in height. Except

in a depression of the summit, where a little soil supports a scanty

growth of shrubs, with a solitary dwarf pine, it is entirely bare.

Everywhere within six or eight feet of the ground, where the surface is

sufficiently smooth, and in some places sixty or eighty feet above, the

rock is inscribed with the names of travelers. Many a name famous in the

history of this country, and some well known to science, are to be found

mixed among those of the traders and travelers for pleasure and curiosity,

and of missionaries among the savages. Some of these have been washed away

by the rain, but the greater number are still very legible. The position

of this rock is in longitude 107° 56', latitude 42° 29' 36". We remained

at our camp of August 1st until noon of the next day, occupied in drying

meat. By observation, the longitude of the place is 107° 25' 23", latitude

42° 29' 56".

Among those who inscribed their names on the rock was Father Pierre DeSmet who later wrote,

"It might be called the great registry of the desert, for on it may be read in large characters

the names of the several travelers who have visited the Rocky Mountains.

My name figures amongst so many others, as that of the first priest

who has visited these solitary regions.

Fremont left a cross on the rock.

Masonic Lodge Meeting, Independence Rock, 1920.

The above photo, taken by Charles Ewing Sproul of

Lander, Wyo., depicts a special Masonic Lodge held July 4, 1920. The meeting commemorated the

first Lodge held in present day Wyoming, July 4, 1862, at Independence Rock by approximately

20 members of a wagon train who were able to vouch for each other.

In 1875, Asa L. Brown, a Past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Washington Territory wrote

Edgar P. Snow, Grand Master of the newly formed Grand Lodge of Wyoming explained that members of the

wagon train desired to celebrate the Fourth of July. He continued with regard

to the Lodge meeting:

"We had just concluded our arrangements for a celebration on the rock,

when Capt. Kennedy's train from Oskaloosa, Iowa, came in, bringing the

body of a man who had been accidentally shot and killed that morning. Of

course, we all turned out to the burial, deferring our celebration until

4 p.m., at which time we were visited by one of those short, severe storms,

peculiar to that locality, which, in the language of some of the boys,

'busted the celebration.' But some of us determined on having some sort

of a celebration, as well as a remembrance of the day and place, and so

about the time the sun set in the west, to close the day, about twenty who

could vouch, and so to speak, intervouch for each other, wended their way

to the summit of the rock, and soon discovered a recess, or, rather

depression, in the rock, the form and situation of which seemed prepared by

nature for our special use.

"An altar of twelve stones was improvised, to which a more thoughtful or

patriotic traveler added the thirteenth, emblematical of the original

colonies, and being elected to the East by acclamation, I was duly

installed, i.e., led to the granite seat. The several stations and

places were filled, and the Tyler, a venerable traveler, with flowing

hair and beard of almost snowy whiteness, took his place without the

western gate on a little pinnacle, which gave him a perfect command of

view for the entire summit of the rock, so he could easily guard against

the approach of all, either ascending or descending. I then informally

opened Independence Lodge, No. 1, on the degrees of Entered Apprentice,

Fellowcraft and Master Mason, when several of the brethren made short,

appropriate addresses, and our venerable Tyler gave us reminiscences of

his early Masonic history, extending from 1821 to 1862. It was a meeting

which is no doubt remembered by all of the participants who are yet living,

and some of those who there became acquainted, have kept up fraternal

intercourse ever since."

According to Casper historian Alfred J. Mokler (1863-1952), writing in

1920, the Square and Compass for the 1862 Lodge were cut from cardboard and the

jewels cut from tins. Following the meeting, the regalia was wrapped in

oil cloth and secreted in a crevice in the rock. The regalia was eventually discovered

by Split Rock rancher Gus Lankin who, in turn, turned them over to Tom Sun. Sun presented them

to Rawlins Lodge No. 5. James Rankin of that lodge carried them to Cheyenne.

The Bible was owned by Edwin Brown who presented it to the Grand Lodge of Wyoming.

When the Cheyenne Temple burned, it was one of the few items saved.

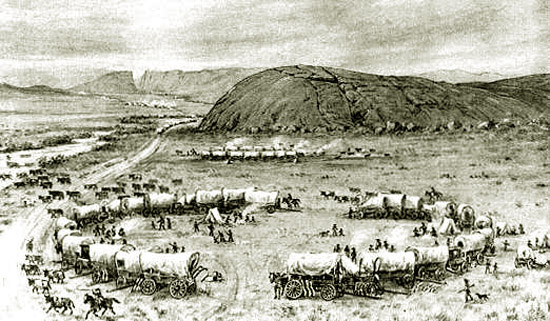

Independence Rock looking west, 1850. In the distance is

Devils Gate.

To the west of Independence Rock, the wagons had to detour away from the Sweetwater where the river wends its way through a narrow gorge

known as Devils Gate. In 1852, Thomas Turnbull (1812-1864) emigrated to California from Chicago.

In his diary, he made note of the area about Devils Gate:

a little way above [Independence Rock] we crossed the Sweet Water by Ford, raised

the Waggon Boxes about 1 Foot & got through safe there was

about 10 logs made into a Crib a man lived there & had a tent &

kept Groceries, charged $1 pr Waggon 100s of Horses, Cattle,

& Mules were here & a little ahead af[t]er leaving the Ford we

went along above the River, tremendous mountains of Rocks

all round the next we passed was the Devils Gate where the

Sweet Water runs through a small gap, a tremendous height

the Rocks seem to be perpendicular at the head of the D G.

to the right is a handsome valley of grass through which the

Sweet water runs but instead of going to the right on acc't of

Teams as far as your eye could carry you on this vast plain

we turned to the left up a creek that runs into the Sweet

Water close by the D. G. about 2m. & found good grass &

plenty Buff dung & Sage for fire camp'd 6 O'clock

Later a poney express station was established at Devils Gate and even later

former Army scout Tom Sun placed corrals for his ranch at the end of the gorge.

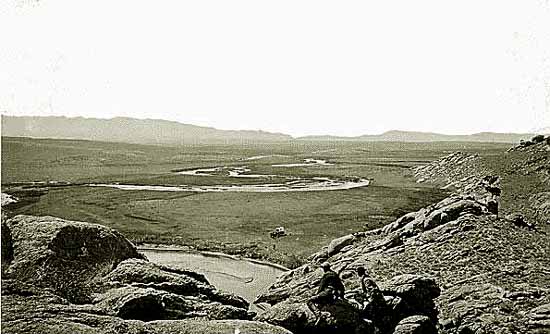

Devils Gate, 1880's

In 1852, Ezra Meeker travelled to Oregon. Fifty-four years later he reversed the journey still travelling by

Ox drawn wagon. At Devils Gate he camped at Tom Sun's post office. He described Devils Gate:

The Devil's Gate and Independence Rock, a few miles distant, are probably the two best known

landmarks on the Trail—the one for its grotesque and striking scenic effect. Here, as at Split

Rock [further west], the mountain seems as if it had been split apart, leaving an opening a few rods wide, through which the Sweetwater River pours a veritable torrent. The river first approaches to within a few hundred feet of the gap, and then suddenly curves away from it, and after winding through the valley for a half mile or so, a quarter of a mile distant, it takes a straight shoot and makes the plunge through the canyon. Those who have had the impression they drove their teams through this gap are mistaken, for it's a feat no mortal man has done or can do, any more than they could drive up the falls of the Niagara.

This year, on my 1906 trip, I did clamber through on the left bank, over boulders head high,

under shelving rocks where the sparrows' nests were in full possession, and ate some ripe

gooseberries from the bushes growing on the border of the river, and plucked some beautiful

wild roses—this on the second day of July, A. D. 1906. I wonder why those wild roses grow there

where nobody will see them? Why these sparrows' nests? Why did this river go through this gorge

instead of breaking the barrier a little to the south where the easy road runs? These questions

run through my mind, and why I know not. The gap through the mountains looked familiar as I

spied it from the distance, but the road-bed to the right I had forgotten. I longed to see this

place, for here, somewhere under the sands, lies all that was mortal of a brother, Clark

Meeker, drowned in the Sweetwater in 1854 while attempting to cross the Plains; would I be able

to see and identify the grave? No.

Geologists have answered Meeker's question. The stream is an "anticedent stream;" that is a stream that not withstanding geological changes in the

landscape such as uplift continues to follow an ancient steambed, eroding down along the original course forming a steep sided

canyon seeming unrelated to local surficial conditions.

Tom Sun was one of those characters from the territorial period of Wyoming who makes repeated appearances in these pages.

Sun came to the United States from Quebec.

Later Sun with Boney Earnest served as a scout with General Miles in the Expeditions against the Indians following

the Battle of Little Bighorn. He, Boney and Frank Earnest served as guides for numerous British hunters. Captain Jack Crawford, popularly known

as the"Poet Scout" and who was a friend of Col. william F. Cody, described Sun:

Tom was a typical borderman. He stood something over six feet high in his moccasins, and was

straight as a tepee pole. He claimed to be a French Canadian, but was so swarthy of complexion

and wore such coarse black hair that the old-timers always believed that Indian blood

predominated in his veins. He was fearless of nature, cool-headed in the face of imminent

danger, a dead shot with the heavy Sharp's rifle which he always carried, and, if all reports

of his life in the far West are true, he had killed Indians sufficient to stock all of the Wild

West shows that ever hit the road. On this subject he was always reticent, and would discuss Idian fighting only with fellow bordermen who were as familiar as he with the the perils of border life.

He was one of the most expert handlers of high-grade profanity whom I ever met, interlarding

his utterances at all times with profane outbursts which fell as tripplingly from his tongue as the waters of a mountain brook ripples over a pebbly bed. When once asked why he so freely used expressions that would be shockingly out of place in polite society he replied, in his French Canadian vernacular:

"Dat's de sort o' talk I was raised amongst, an' I can express myself better in dat dan in any

odder way so I see no advantage in changin' to straight talk."

Looking west from the top of Devils Gate. Photo by William Henry Jackson, 1870.

Sun's Ranch remained in his family until 1997 when it was sold to the Latter Day Saints Church and became the

Mormon Handcart Historical Center.

Devils Gate, 1922.

To the west of Devils Gate, the pioneers came across the "Ice Slough."

Turnbull made note:

Friday 18th. left Sweet "W. at 6 Oclock in the morning just

after starting the Wind ridge mountains made there appearance

all covered with Snow About 2 Hours travel we came

to the Alkali Swamp we saw some men digging for Ice, it is

said that Ice can be found 2ft under ground, saw one deer

plenty ground Dogs. Cattle lying dead on the Road, passed

over 1000 head of Cattle, the road the most of the way very

heavy Sand & Gravel * * *.

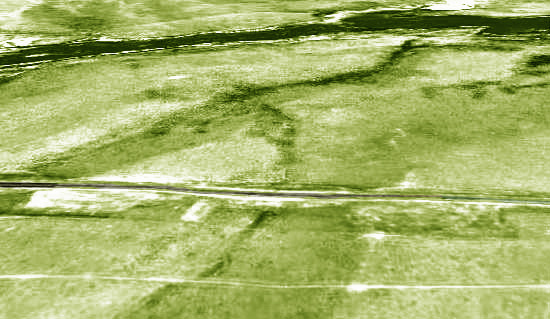

Arial View of Ice Slough, looking north toward the

Sweetwater

The slough provided in the heat of summer unusual

refreshment. In his notes J. Goldsborough Bruff wrote,

"...by digging a couple of feet, ice is obtained. The surface is dug up all

around by travelers - as much from curiosity as to obtain so desirable a

luxury in a march so dry and thirsty...."

Indeed, the Belshaw party from Lake County, Indiana, paused at the Slough on July 4, 1853. Capt.

George Belshaw noted in his diary that lemonade was made with the ice,

"It relished first rate."

In the Slough, peat built up over the tundra-like sub-surface, insulating

the frozen water below from the summer heat. Today the slough is a broad green swale leading north toward the

Sweetwater. Because of

changes to the drainage wrought by irrigation, the sub-surface ice no longer forms.

Music this page: |

OH, SHENANDOAH

Oh, Shenandoah, I long to hear you.

Away, you rolling river!

Oh, Shenandoah, I long to hear you,

Away, I'm bound away,

'Cross the wide Missouri.

The white man loved an Indian maiden,

Away, you rolling river!

With notions his canoe was laden,

Away, I'm bound away,

'Cross the wide Missouri.

Oh, Shenandoah, I love your daughter,

Away, you rolling river!

For her I've crossed the stormy water,

Away, I'm bound away,

'Cross the wide Missouri.

Farewell, my dear, I'm bound to leave you.

Away, you rolling river!

Oh, Shenadoah, I'll not deceive you,

Away, I"m bound away!

'Cross the wide Missouri.

|

Next page: The Pony Express, The Pacific Telegraph.

|