Fort Bridger, Judge Carter's meat house. ice house, and stables, approx. 1926.

Once recovered from the yellow fever, Carter moved to Boone County, Missouri. In 1848, he caught the gold rush fever and with his brother went to

California. Like for many others, California proved not to be golden. He returned to Missouri via way of

Nicaragua and Cuba. Following the "Pig War," General Harney was stationed in Missouri and thus as previously noted

the Carter and Harney were brought together again. For Carter, it was a matter of being in the right place at the

right time.

Judge Carter's meat house and mess hall, approx. 1926.

The mess hall is the one-story building to the left of the entrace to the meat house.

In order to finance his new business as Sutler at Fort Bridger, Carter made arrangements for

a $200,000.00 line of credit with Robert Campbell. With the outbreak of the Civil War, a new danger to

Carter's business appeared. In the Spring of 1862, the Army withdrew all of its troops from

Fort Bridger.

Judge Carter's mess hall and meat house. Photo by Arthur Rothstein, 1940. Note again

the installation of new protective roof above the original roof of the meat house and mess hall.

Carter received the contract to move all of the Army equipment to Denver. It took 40 wagons to

move the equipment, but the Fort was then left undefended. At his own expense, Carter raised and armed a civilian

company for the defense of the Fort until finally in December, 1862, a company of California

Volunteers manned the Fort.

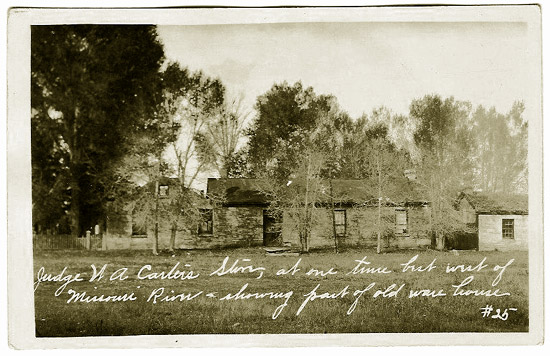

Casson in front of remains of Carter's Store and Warehouse, Ft. Bridger, undated, but believed to be from the early 1900's.

Remains of Carter's Store and Warehouse, Ft. Bridger, approx. 1928.

With the end of the War, Carter then began an expansion of his

business. Thus, in 1869, Gen. James F. Rusling in his book The Great West described the growth

of Carter's business:

Gradually his sutler-store had grown to be a trade-store with the Indians, and passing emigrants; and in 1866 he reported his sales at $100,000

per year, and increasing. He was a shrewd, intelligent man, with a fine

library and the best eastern newspapers, who had seen a vast deal of life in

many phases on both sides of the continent, and his hospitality was open-handed and

generous even for a Virginian.

Post Trader's Store, Ft. Bridger

But at the same time, other perils arose. Congress considered the abolishment of sutlers and their replacement with

government run stores. This necessitated Carter traveling to Washington to lobby for the

preservation of his business. The compromise reached enabled existing sutlers to continue as post traders provided

that they live on post.

Former Residence Judge William A. Carter, Fort Bridger, undated but believed to be early 1900's. The house

burned down in the 1930's.

By 1874, Carter's business activities grew even more extensive. E. A. Curley described

Carter's enterprises:

He is a post trader, and a general wholesale and retail merchant; he is a

lumberman, with several sawmills running in the mountains; he is a stockman,

with some 2,000 head of cattle; he contracts for forage, fuel, mean &, for

the government; he builds roads and bridges on his own account; and he drills

though the Wyoming rock for oil.

In 1881, Carter received a contract from the Army to layout a wagon road from Fort Bridger to

Brown's Hole in Utah. Although, Carter was then 63 years old, he personally supervised the

laying out of the road. In the cold and damp of the winter in the Uinta Mountains, Carter suffered from

exposure and returned home to Fort Bridger and died. His son, Willie, then a student at

Cornell, returned home and completed the contract. Carter's widow, Mary Hamilton Carter, continued the business until

the fort was abandoned in 1890.

Next page: Fort Bridger continued.

|