|

Camp Apache, Arizona Territory, 1877

Some 800 miles to the south of the hills and cottonwood of the Upper Chugwater Valley lies a desolate,

arid, hot valley surrounded by the Gila Mountains to the north, the Mesca Mountains to the west, and

Pinaleno Mountains to the south. To this area, far from the piñon and pine where they resided, the

government decreed that all Apache, including the Ciricahua, were to be concentrated on a

reservation known as San Carlos. In May, 1885, some of the Ciricahua led by

Naiche, son of the great chief Cochise, and Geronimo, "escaped" from the reservation. Their departure was

as a result of a dispute involving the brewing of corn beer in violation of government rules. Thus, ensued the

last of the Apache wars. As indicated by the unknown author on the previous page, Tom Horn was

drawn into this conflict. The extent of his participation is as much a matter of

bitter and acrimonious debate as is his involvement in various murders in Wyoming. Was he,

as portrayed in movies, responsible for the capture of Geronimo, or was he a liar, guilty of

stealing credit rightfully belonging to a young West Point graduate, Charles B. Gatewood?

Horn undoubedly had an ability with languages and had picked up both Spanish and

Apache. He also had over the years picked up an ability as a tracker. Thus,

it was only natural that he was employed by the Army as a scout and interpreter. As an interpreter,

he was employed on Emmet Crawford's ill fated 1886 expedition into Sonora. On January 11, 1886,

Captain Crawford's company ran into some Mexican irregulars. Lt. Marion P. Maus, second in command, later reported:

A party of them [the irregulars] then approached and Captain Crawford and I went out about 50

yards from out position in the open and talked to them. I told them in

Spanish that we were American soldiers, called attention to our dress and

said we would not fire. Captain Crawford then ordered me to get back and ensure no

more firing. I started back, when again a volley was fired. When I turned again

I saw the Captain lying on the rocks with a wound in his head, and some of his

brains upon the rocks. This had all occurred in two minutes. There can be

no mistake. These men knew they were firing at American soldiers at this time.

In the ensuing fire fight, among those wounded was Tom Horn. Ultimately, as a result of the superior

marksmanship of the Americans and Apache scouts, the Mexicans displayed a white

flag of truce. After two days, the Mexicans and Americans separated with the Mexicans

keeping some of the American mules.

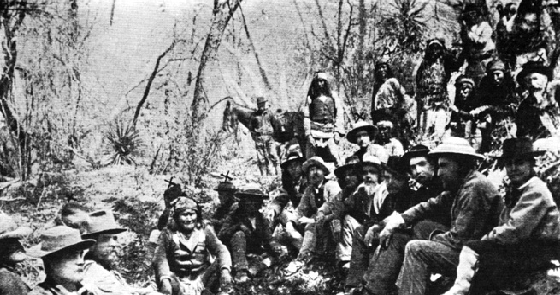

Geronimo and Gen. Crook at Cañon de Los Embudos, Sonora, March 27, 1886,

photo by Camillus S. Fly.

Left to right, seated: Shipp; Faison; Captain Roberts; Geronimo; Jesus Aguirre;

Nana; Sgt. Major Noche; Lt. Marion P. Maus; interpreters Vasquez and Besias; Montoya; Bourke; Gen. George F. Crook;

and Charley Roberts. Behind Shipp, Faison and Capt. Roberts is an unknown Apache. Behind Geronimo are

Cayetano and an unidentified Apache. Behind Vasquez and Besias are Daly and Chihuahua. Behind Crook are

an unidentified Apache, Yanozha, and Strauss. Standing are two unidentified Apaches, Tommy Blair with

Crook's mule named "Apache," Fun; Ulzanas, Laziyah, and two other Apaches.

C. S. Fly was a Tombstone, Ariz. photographer. His photographic Gallery on Allen

Street was located immediately next to the OK Corral and the vacant lot in which the famous

gunfight occurred. Indeed, it was Fly, armed with a Henry rifle, that disarmed the

dying Billy Clanton immediately after the fight.

Charles B. Gatewood

Charles B. Gatewood

Following Geronimo's surrender to Gen. Crook, on the way back to Arizona, Geronimo changed his mind and

again escaped. As a result on April 1, Crook resigned his Command and was replaced on the 11th by

Gen. Nelson Miles. After three months of unsuccessful pursuit, Miles determined to

send an officer who was personally known by Geronimo to meet with the chief. This decision must have

been particularly galling to Miles, as it meant a reversion to the tactics of George

Crook. The only officer who personally knew Geronimo and his men was Lt. Charles B. Gatewood, known to the Indians as

Bay-chen-daysen, "Long Nose." Gatewood would later

serve at Fort McKinney, Wyo., at the time of the Johnson County War and was

injured in the bombing of the barracks by the so-called "Red Sash Gang."

Gatewood, tall, thin, and sickly, at first refused

the assignment into Mexico because of his ill health, but he was finally induced to undertake

the mission by a promise of being appointed Miles' Aide de Camp.

While on the mission into Mexico,

Gatewood's health continued to visibly deteriorate, but he was refused a requested

medical discharge by Leonard Wood. On

August 25, after a month's search, Gatewood, with a contingent comprised of

interpreters Martine (a Nednihi Chiricahua), George Wratten, Jesus Yestes, and Tom Horn; a soldier; and

four Apache Scouts, came into contact with Geronimo's

band at a bend of the Bavispe River.

Party from Geronimo Campaign.

Some question exists as to the identity of the persons in the photo. A handwritten note with the

photo identified the individuals as the party that captured Geronimo. If so, the

individuals would include

Charles Gatewood, Martine, George Wratten, Jesus Yestes, Tom Horn, Kayitah, and possibly Tex Whaley and Frank Huston.

An identification has also been made left to right: Groves, Mr Stevens, Chino, Stugh (front), Funston??, Tony,

Furgerson, Leonard Wood.

After anxious moments, Geronimo appeared armed with a Winchester. Setting his weapon aside,

Geronimo greeted Gatewood and inquired after Gatewood's obvious sickly appearance.

After a full day's negotiation, the next morning Geronimo agreed to surrender

to Gen. Miles, based on Gatewood's personal promise that Miles was honorable and his word was good; and on condition

that Gatewood would personally travel with Geronimo's band to the place of surrender. American troops were to

travel separately. It was agreed that the Chiricahuas would keep their

weapons until they reached the place of surrender. Thus, the two bands separately traveled to Skeleton Canyon on the

American side of the border. On the course of the journey when the two groups camped near each other,

Lt. Abiel Smith in charge of the American unit, proposed to disarm the Apache in violation of

Gatewood's agreement. Word of the proposal reached Geronimo, who, fearful that the Americans

planned on murdering his band, again threatened to

flee. Only intervention by Gatewood with Geronimo, and an angry confrontation by Gatewood with Smith and Leonard Wood,

saved the situation.

Geronimo (on right), photo by C. S. Fly

With the surrender, Gatewood became, to Miles' consternation, the man of the hour with

the press. Miles' actions have became a source of

continuing controversy. Miles ordered Geronimo, his band, and the scouts who had loyally

served the United States, exiled to Ft. Pickens and Ft. Marion in Florida and later to a

fort in Alabama. Geronimo technically remained a prisoner of war for the remainder of his life and

was never permitted to return to his native land. All who participated in the capture of Geronimo, except

Gatewood, were honored and received promotions. On November 8, 1887, a celebratory reception was held at

the San Xavier Hotel in Tucson to honor the officers who brought the Apache War to an

end. Gatewood was not invited. In his post-humously published autobiography, Horn took credit for

the actions of Gatewood, indicating that it was he, Horn, whom Geronimo trusted and it was he,

Horn, who convinced Geronimo to surrender.

The autobiography is the only evidence of Horn's responsibility. Officially,

Miles and Henry Lawton (later Major General) were given credit. Gatewood never received

another promotion. He was nominated for the Medal of Honor for his actions in

entering Geronimo's camp outnumbered, but the Medal was denied on the basis that Gatewood never came

under actual hostile fire.

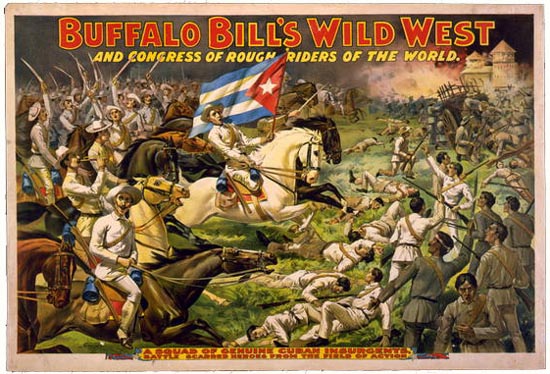

Poster for Buffalo Bill's Wild West, 1898

In 1898 with the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor, demand for war against

Spain swept the country. In New York, Col. Wm. F. Cody's Wild West Show featured

a troup of Cuban rebels who unfurled the Cuban flag while the cowboy band played a

Cuban anthem and the audience yelled "Cuba Libre." Col. Cody, himself, offered

to raise an army of 30,000 American Indians. Thus, John Hay's

"splendid little war" broke out with Spain. Almost immediately Theodore Roosevelt

ordered a Brooks Brothers custom made uniform and

organized a volunteer cavalry troop of which he was to be second in command. Leonard

Wood was to be in command.

The troop was composed mostly of cowboys but also included a few

Indians and wealthy polo-playing easterners. In Arizona, a former sheriff of

Yavapai County, William Owen "Buckey" O'Neill, under whom Horn had served as a

deputy, organized a troop, later to be Troop "A" of the Rough Riders.

William Owen "Buckey" O'Neill

Of O'Neill Roosevelt

later wrote in his 1899 The Rough Riders:

There was Bucky O'Neill, of Arizona, Captain of Troop A, the Mayor of Prescott,

a famous sheriff throughout the West for his feats of victorious warfare

against the Apache, no less than against the white road-agents and

man-killers. His father had fought in Meagher's Brigade in the Civil War;

and he was himself a born soldier, a born leader of men. He was a wild,

reckless fellow, soft spoken, and of dauntless courage and boundless

ambition; he was stanchly loyal to his friends, and cared for his men in

every way.

In July, shortly before Roosevelt's famous charge, O'Neill was killed at Kettle Hill.

But O'Neill in some aspects was less than rough and tough. When Dennis Dilda, a condemned murderer, was

hanged in 1886, O'Neill commanded the Honor Guard. When the trap dropped, O'Neill

fainted dead away.

Following the Apache wars, Horn worked in the area of Pleasant Valley, Ariz. (Now known as "Young."),

to the northwest of the San Carlos Reservation. There, he worked on a ranch owned by Tempe hotelier Robert Bowen.

In August 1888, Horn participated with Glenn Reynolds in a lynching of three suspected rustlers.

In November, Reynolds was elected as sheriff of Gila County. Horn was appointed as a deputy. Reynolds,

hmself, was killed in a shootout with the former Apache Scout Haskay-bay-nay-natyl, the Apache Kid.

The Kid was so-called allegedly because the whites had diffculty pronouncing his name. In the

shootout, another deputy, W. A. "Hunky Dory" Holmes died of an apparent heart attack. The Apache

Kid escaped, his fate unknown to this day. Various sightings and reports of

the Kid's death were received as late as the 1920's. It is

commonly believed that Horn involved himself in the Graham-Tewksbury feud (the "Pleasant Valley War") and that

Horn, himself, may have been a precipitating cause with the killing of Mart Blevins in 1887. Some of

the Blevins children had been suspected of rustling. Adding fuel to the fire was the

introduction of sheep into the area. Whether Horn, in fact, caused the war remains a

matter of speculation. Zane Grey, preparatory to writing his The Last Man,

spent three years investigating the cause of feud. In his forward, Grey wrote:

I never learned the truth of the cause of the Pleasant Valley War, or if I

did hear it I had no means of recognizing it. All the given causes were

plausible and convincing. Strange to state, there is still secrecy and

reticence all over the Tonto Basin as to the facts of this feud. Many

descendents of those killed are living there now. But no one likes to talk

about it. Assuredly many of the incidents told me really occurred, as, for

example, the terrible one of the two women, in the face of relentless

enemies, saving the bodies of their dead husbands from being devoured by

wild hogs.

Following the Pleasant Valley War, Horn drifted to Prescott where he worked as

a deputy for Sheriff O'Neill. Thus, it would not be unexpected that

among those from Prescott who volunteered was

Tom Horn.

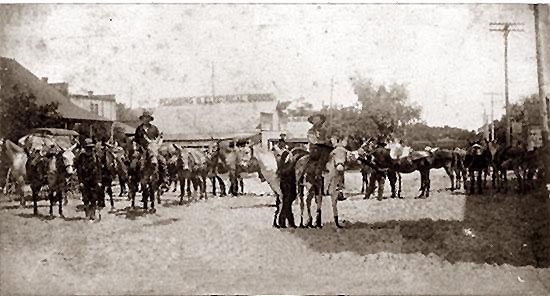

Rough Rider mules, Franklin Street, Tampa, Florida,

1898. Photo, courtesy Tampa-Hillsborough County Library System.

It is impossible to state with certainty that the

above photo shows Horn in Tampa. Names of the wranglers were obviously not taken down.

Conditions in Tampa were miserable. Camp Palmetto had to be abandoned because of

unhealthy conditions. The Rough Riders were assigned to Port Tampa where many

suffered from the tropical heat, humidity, and, after sundown or in the shade,

great swarms of mosquitoes. While the woolen uniforms may have helped provide

protection from the mosquitoes, they were of little help against the unrelenting heat.

Nor did they help against the chiggers which infested the grass and Spanish moss. The chiggers

would burrow beneath the skin at the cuff or belt line causing large red welts. The welts gave

rise to the local name for the insect, "red bugs." As discussed in the side note below,

Horn never saw active duty with the Rough Riders

in Cuba. Although the Rough Riders had a regimental pack-train, it had to be left behind in Tampa. Roosevelt

continually complained that there was no transportation in Cuba. Roosevelt noted:

Again and again we sent down

improvised pack-trains composed of officers' horses, of captured

Spanish cavalry ponies, or of mules which had been shot or abandoned

but were cured by our men. These expeditions--sometimes under the

Chaplain, sometimes under the Quartermaster, sometimes under myself,

and occasionally under a trooper--would go to the sea-coast or to the

Red Cross head-quarters, or, after the surrender, into the city of

Santiago, to get food both for the well and the sick.

Horn was one of the many who came down with malaria. Troops who came down with

typhoid or malaria in Tampa had to be evacuated by hospital train to either

Ft. McPherson, Georgia, or Pablo Beach near Jacksonville. Some 1200 passed through

Ft. McPherson by the end of August and 1400 through Pablo Beach by November. Indeed, American

casualties in the splendid little war were 496 killed in action, 202 died from wounds, and

5,509 died from tropical diseases. Dr. Charles F. Kieffer, an army surgeon, reported that in one unit of

approximately 575 men, the average sick daily sick call was 120. He reported that

"at least 95 per cent of the command [came down with malarial fevers]—75 per cent had two attacks and about 40 per cent had three attacks to the time of leaving the island."

Dr. Kieffer is believed to have climbed Grand Teton in 1893 when he was on temporary duty at

Fort Yellowstone.

WAS HORN WITH THE ROUGH RIDERS OR SERVE IN CUBA?

Although it is popularly regarded that Horn saw duty in Cuba with Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders such service is

doubtful. Jay Monaghan in his

Last of the Bad Men, Bobbs Merrill, Indianapolis, 1946, reprinted as

Tom Horn, Last of the Bad Men University of Nebraska Press, 1997, notes that original (or indeed for that matter,

secondary sources) as to Horn in Cuba are "fugitive." Monaghan writes:

"The Spanish-American War episodes in this

book have been fugitive. Books about this period are

plentiful but references to Tom Horn are

scarce. In the testimony taking by the committees investing

the conduct of the War Department a man who resembled Tom Horn is

mentioned but not named. General Leonard Wood told me a little that he

remembered of Tom in Cuba. Lu Dick, whose father, Senator C. W. F. Dick of Ohio, landed at

Daiquiri with Shafter, repeated the stories he had heard. So did

Luther Stewart of Jensen, Utah, who was among the

enlisted men. Miss Florence Spofford found for me in the

General Accounting Office in Washington the data on Horn's rank and pay in the

trasportation service."

The main source of Horn's alleged service in Cuba is Glendolene Mrytle Kemmell's scant two page

account appearing at pages 288 and 289 of Horn's purported autobiography, Life of Tom Horn, Government Scout and Interpreter, Written by Himself, A

Vindication, Louthan Book Company, Denver, 1904. The account suggests that Horn arrived in Tampa only one day behind the Rough Riders; that Horn was

indirectly responsible for the victory at San Juan Hill; and Horn was a personal acquaintance of

General Shafter and, in a personal audience with the General, was addressed by Shafter as "Colonel."

Thus, except for dates of enlistment and mustering out, all that is known of

Horn in the Spanish-American war is based on oral remembrances taken down many years after the

events. Monaghan places Horn in the center of the widely reported swimming of the mules and horses ashore at

Daiquiri, Cuba. Indeed, Miss Kemmell's account has Horn in charge of the

unloading at Daiquiri. Yet, nothing can be found that indicates that Horn was in fact there.

Until 1912, scouts, packers, teamsters, and cooks were civilians employed by the Quartermaster.

Thus, Horn was a civilian and would not have been included on any military rolls.

If, Horn was with Shafter, he would not have been a part of the Rough Riders. As noted above,

The Rough Riders arrived in Tampa from Texas on June 1, 1898. The Rough Riders'

regimental pack team was left behind in Tampa for lack of transport. When the Rough Riders landed in

Cuba, they had but one horse. Indeed, Roosevelt had to,

in essence, steal a ship that had been consigned to other units even to get to

Cuba. Additionally, Monaghan notes that Horn enrolled at Tampa, Florida, on 23 April 1898, long before the Rough Riders arrived

at the port city. Horn was discharged on

6 September 1898. The Rough Riders, including the ill, were discharged on 15 September 1898. Thus, on three accounts,

Horn could not have been with the Rough Riders in Cuba.

That, however, does not resolve the question of whether Horn saw duty in Cuba.

Both Monaghan and Dean Fenton Krakel, The Saga of Tom Horn: The Story of a Cattlemen's War, suggest that

Horn had Yellow Fever. If Horn was in Cuba, it was most likely malaria. See Roosevelt's The Rough Riders.

Yellow Fever, known to troops in Cuba as "The Black Vomit," had an 85% mortality rate. To prevent

the disease from spreading, troops suffering from fever were divided into "well" and "sick" camps. Those who came down

with the fever were not permitted to return to the United States but were, instead, hospitalized at

Siboney. See The Yellow Fever and the Reed Commission, 1898-1901,

University of Virginia Health System, Hench-Reed Yellow Fever Collection. Indeed, the situation with regard to

Yellow Fever in Cuba, even before the destruction of the Spanish Fleet on 3 July 1898, was such that Gen. Miles determined that

he could use none of the troops in Cuba in the subsequent Puerto Rico campaign and that entirely

fresh troops from Tampa would be utilized. See Gen. Miles' account in "The War with Spain--III,"

The North American Review, July 1899. It is doubtful that Horn was in Cuba.

Interestingly, however, newspaper accounts of Horn's execution in 1903 reported that Horn, in fact,

saw duty in the Spanish-American War, but not in Cuba but in Puerto Rico. Thus, the

Los Angeles Herald, November 21, 1903, reported:

Tom Horn was born in Scotland county, Missouri, November 21, 1860. He was a celebrated

army scout, Indian fighter and cattle detective. He was the scout in charge of the party

that captured Geronimo and was chief of scouts under General Miles in his Porto Rico

campaign. In 1892 Horn participated in the raid against the cattle rustlers of Johnston [sic] county,

Wyoming.

Horn was a self-educated man. He spoke German, Spanish, Apache and a number of Indian languages fluently.

There was no mule or pack shortage in Puerto Rico. As observed by Monagahan much has been written of the Cuban

campaign. Little, however, is available as to the campaign in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico fell like

an overripe apple. Not withstanding leaks as to Miles' planned invasion of Puerto Rico in the Washington

papers, of which Miles complained vehemently, the war lasted less than 19 days. Karl Stephen Herrmann in his 1907,

A recent campaign in Puerto Rico by the Independent Regular Brigade under

command of Brig. General Schwan, Boston, E. H. Bacon, 1907, describes

General Schwan entering Mayaguez at the head of his troops, "colors flying and band playing."

Another reason for no reports of the war on the island is given by

Herrman:

Because we had no Volunteers with us, we were not granted even one little word-spattering newspaper scribe, and so relinquished at the outset any fugitive hopes of glory that otherwise might have been entertained. We were out for business,--hard marching, hard living, hard fighting,--and the opening vista was fringed with gore. We were none of us the darlings of any particular State, nor the precious offspring of a peripatetic statesman with a practised pull. We were at no time decimated by disease through ignorant or insubordinate

disregard of the primary principles of hygiene. We didn't write long wailing letters home because we were obliged to sleep on the damp ground, and had neither hot rolls, chocolate, nor marmalade for breakfast. We were ragged, hungry, tough, and faithful. In other words, we were regular army men, and, most distinctly, not Volunteers.

There is a personality peculiar to the professional soldier, even though he be but a half-fledged recruit, that defies analysis and baffles description. He is of course built from the same clay as his brother of the Volunteers; but the latter is a tin god, and the former is a devil. Yet the difference does not spring from anything more fundamental than environment, and therein lies the solace of the other fellow. Putting aside all odious comparisons and limiting myself to a view of the regular army man as I know him, I can simply say that in the eight months during which I underwent in his company hard knocks and privations without number I could not have found a more truly satisfactory

comrade and friend. He doesn't, on the average, know much about books; nor did he ever hear of the Etruscan Inscriptions or the Pyramidal Policy of the Ancient Egyptians. He takes a grim delight in smashing the English language into microscopic atoms at a single blow. He is more fond of women, horses, and prize-fighting than is good for him. He will steal when he is hungry, lie to save his skin, curse most terribly on trifling provocation, and spend, to his last sou markee, his hard-won wage on adulterated drink.

|

"He's a devil an' a ostrich

an' a orphan-child in one." |

But he will stand his ground in action while there is ground to stand on; he will throw his life away at a moment's notice for the flag, or a chosen comrade, or a worthless girl; he will march and starve and thirst world without end if he has a leader who holds his confidence; and he is, on the whole, a rather fine specimen of the true American--being usually Irish or German.

Therefore, one may speculate as to whether the accounts of Horn serving in Cuba or Puerto Rico is or is not

accurate. Miss Kemmell's version is undoubtedly as a result of Horn's braggadocio. Most likely,

because of the time frames involved, is that Horn came down with malaria in Tampa even

before the ships sailed and was discharged in September when able to return home.

|

Upon his return to Wyoming, Horn resumed his prior employment, ostensibly as a bronco

buster at $125.00 a month, for various ranches along the upper Chugwater.

Music this page: Marching to Cuba. For lyrics see Fort D.A. Russell.

Next page: the murder of Matt Rash and Isom Dart.

|