|

>

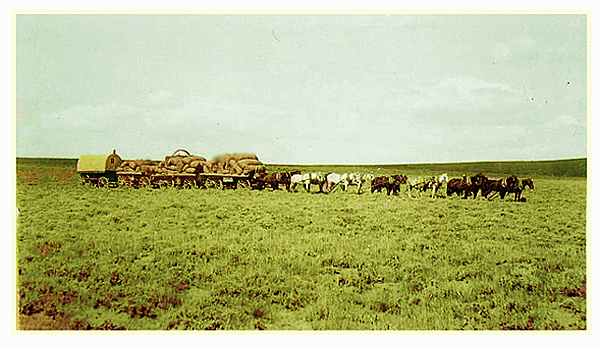

Wool Wagons near Cody.

Wool growers located near railroads had a distinct competitive advantage. Until railroad pushed into the interior of Wyoming, wool

had to be transported to the nearest railroad in wagons hitched together in "string teams" consisting of two or three wagons pulled by

10, 12, or even 16 pairs of horses.

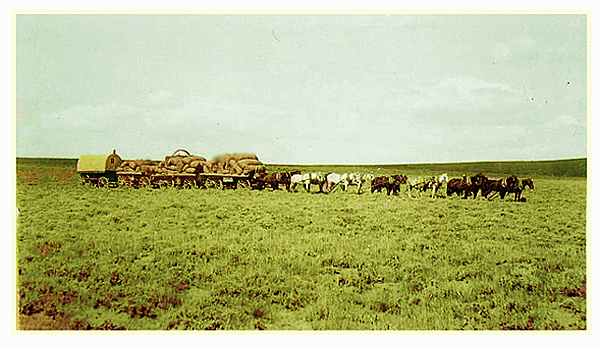

Sixteen Horse Hitch near Buffalo, 1898.

Sometimes the nearest railroad could be as much as 200 miles away. An early government surveyor, W. R. "Roy" Bandy" commented on the

wool trains pulling through Garland near Cody:

Garland’s most interesting attractions for me were long freight teams of horses pulling two or three wagons

loaded with sacks of wool. Ten or more horses hitched two abreast in a

long string were driven by one man riding one of the wheel horses (the

team next to the wagon). It was marvelous how one driver could turn the

outfit around in the street, and maneuver the heavy wagon into position

for loading freight cars. They did it by using a jerkline to guide the

lead team. The swing team hitched to the front end of the wagon tongue

played a most important role when going uphill on sharp curves. Often,

they would have to step over the draw chain and pull at right angles to

prevent the wagon from going off the road.As quoted in "Running Line: Recolltions of a Surveror, U. S., Dept. of Interior, 1991.

"The "jerkline" referenced is also sometimes referred to as a "G String." For explanation of

jerklines and the steering of freighters, see

Encampment.

Wool Wagons, Park Avenue, Meeteetse, approx. 1906.

Stewart Culin in his 1900 160-mile trip from Casper to Lander marveled

at the long lines of wool wagons and the stacks of wool along side the road awaiting pick

up. See "A Summer Trip Among the Western Indians," Bulletin of the Free Museum of Science and Art, University of Pennsylvania, January 1901.

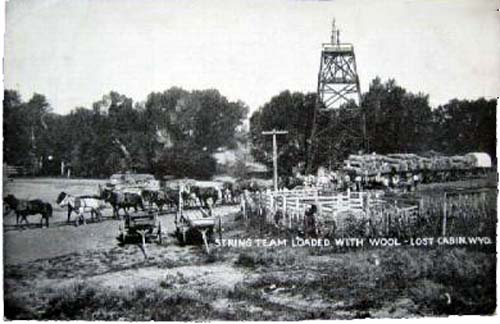

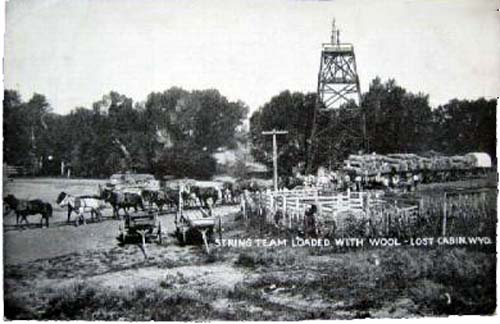

Wool wagons leaving Lost Cabin, Wyoming, for the railroad at Casper.

Note the sheep wagon at the end of the train. The reason for the sheep wagon is that most freighters would not leave

their rigs when camped. The 70-mile trip to Casper could require several nights on the road. Between

Casper and Wolton and Casper was a stretch heavy with gumbo that was known as

"the Freighter's Delight and would bog down the wagons. Gumbo would "ball up" on the wheels, axles, and breaks, so much

so much that many freighters would remove the brake blocks before going through the gumbo. In at least one instance an

Orgonian freighter had to spread out his cargo of beans in the road in order to get the wagons through.

For a number of years, the road was lined with bean plants.

Wool wagons crossimg Powder River, 1898.

It could take three to seven days to complete a one hundren mile round trip. The railroad pushing in from

Casper to Lander by-passed Lost Cabin. See also undated fourteen horse hitch in next photo.

Fourteen horse wool wagons.

The freighters in many instances were what would now be call "independent truckers;" that is, they owned their own

rigs and would pick up wool in sheep country, transport it to the railroad and then pick up freight for the return

trip.

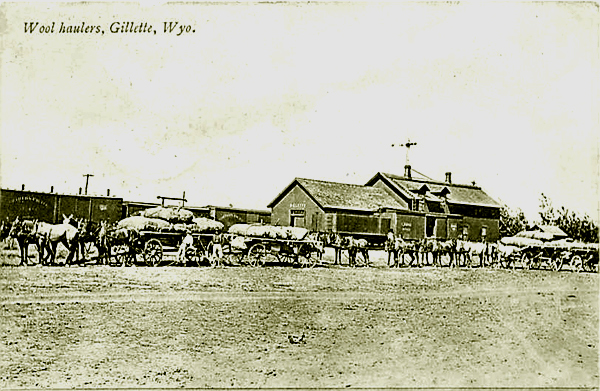

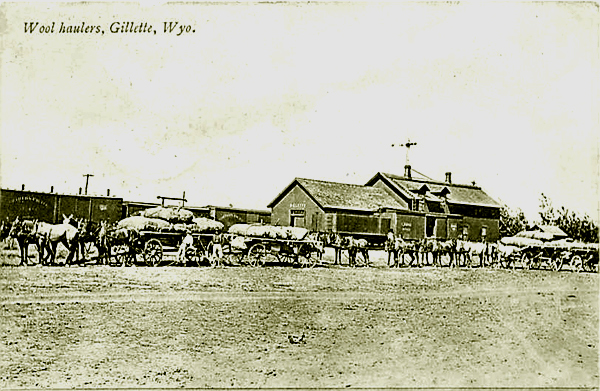

Wool Trains ready for unloading, Gillette.

Next Page, The Big Horn Sheep Company.

|