Northern Montana Bison. Photo by L. A. Huffman, 1880

The Great Plains were divided into three great buffalo ranges, the northern in Wyoming, Montana, Dakota Territory, and in

the British territories north of the Medicine Line; the central in Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado; and the southern in

Texas, Indian Territory, and New Mexico. The first to go was the central. On the Central Plains by the time of the arrival of

of the Atchison, Topeka and Sante Fe to Raton Pass in 1879, the buffalo were pretty much gone. Bone hunting held on for another year.

the The hunters then moved south to

Texas, and then to the northern range. In Montana, the first railroad, the Utah and Northern Pacific, did not arrive until December 1881.

The Northern Pacific was completed across the state in 1883. In the meantime, James Hill was pushing what was to become the

Great Northrn westward reaching Butte in 1888. Thus on the northern range, the slaughter continued unabated for a bit longer. In the winter of 1881-1882, victor Grant "Vic" Smith (1850-1925) equalled

Charles Rath's record of bison in one hour. The same winter is is reputed to have slain some

5,000 bison. While in the popular mind we may have an immage of Buffalo Bill shooting the bison from a galloping

horse, the records were set by shooting from a "stand," that is from a fixed position. The process entailed getting ahead of the

herd and shooting the lead bison. Good buffalo hunters had a sucess rate of killing over 80% on the first shot.

Smith reported used as many as 20,000 cartidges practicing and hunting in a single year. Smith after the near extinction of the bison

on the northern plains acted as

a guide for wealthy easterners including Medora, Dakota Territory ranchman Theodore

Roosevelt. Theodore Roosevelt in 1885, noted the slaughter on the northern Plains:

No sight is more common on the plains than that of a bleached buffalo skull; and their countless numbers attest

the abundance of the animal at a time not so very long past. On those portions where the herds

made their last stand, the carcasses, dried in the clear, high air, or the mouldering

skeletons, abound. Last year, in crossing the country around the heads of the Big Sandy,

O'Fallon Creek, Little Beaver, and Box Alder, these skeletons or dried carcasses were in

sight from every hillock, often lying over the ground so thickly that several score could be

seen at once. A ranchman who at the same time had made a journey of a thousand miles across

Northern Montana, along the Milk River, told me that, to use his own expression, during the

whole distance he was never out of sight of a dead buffalo, and never in sight of a live one. Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

Roosevelt also explained the near extinction of the bison:

GONE forever are the mighty herds of the lordly buffalo. A few solitary

individuals and small bands are still to be found scattered here and there

in the wilder parts of the plains; and though most of these will be very

soon destroyed, others will for some years fight off their doom and lead

a precarious existence either in remote and almost desert portions of the

country near the Mexican frontier, or else in the wildest and most

inaccessible fastnesses of the Rocky Mountains; but the great herds, that

for the first three quarters of this century formed the distinguishing and

characteristic feature of the Western plains, have vanished forever.

It is only about a hundred years ago that the white man, in his march

westward, first encroached upon the lands of the buffalo, for these animals

had never penetrated in any number to the Appalachian chain of mountains.

Indeed, it was after the beginning of the century before the inroads of the

whites upon them grew at all serious. Then, though constancy driven westward,

the diminution in their territory, if sure, was at least slow, although

growing progressively more rapid. Less than a score of years ago the great

herds, containing many millions of individuals, ranged over a vast expanse

of country that stretched in an unbroken line from near Mexico to far into

British America; in fact, over almost all the plains that are now known as

the cattle region. But since that time their destruction has gone on with

appalling rapidity and thoroughness; and the main factors in bringing it

about have been the railroads, which carried hordes of hunters into the

land and gave them means to transport their spoils to market. Not quite

twenty years since, the range was broken in two, and the buffalo herds in

the middle slaughtered or thrust aside; and thus there resulted two ranges,

the northern and the southern. The latter was the larger, but being more

open to the hunters, was the sooner to be depopulated; and the last of the

great southern herds was destroyed in 1878, though scattered bands escaped

and wandered into the desolate wastes to the southwest. Meanwhile equally

savage war was waged on the northern herds, and five years later the last

of these was also destroyed or broken up. The bulk of this slaughter was

done in the dozen years from 1872 to 1883; never before in all history were

so many large wild animals of one species slain in so short a space of time. Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

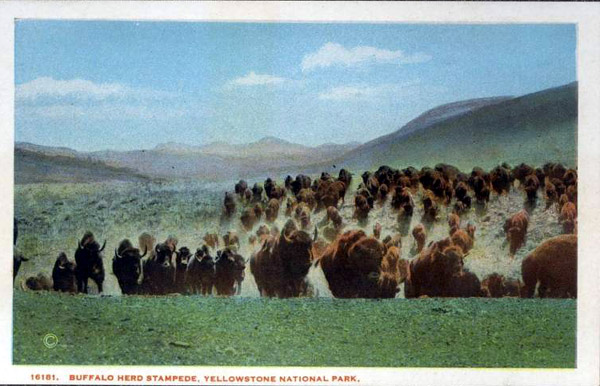

Stampede of Yellowstone Bison, approx. 1905, Photo by Detroit Publishing Company

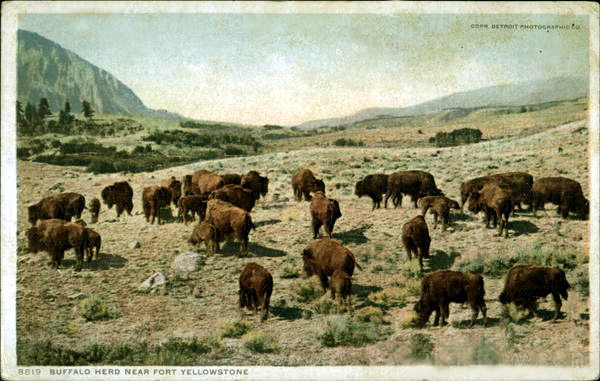

By 1890, it is estimated that only 750 bison were

left in the United States. Today's herds are descended for the most part from 23 bison in Yellowstone's

Pelican Valley, a herd developed by Charles J. "Buffalo" Jones, and the Goodnight-Thayer Cattle Company herd of 250 animals. That herd owed its

existence to the adoption and care of orphaned calves by the wife of Charles

Goodnight, Mary Ann Dyer Goodnight.

Yellowstone Bison, approx. 1905, Photo by Detroit Publishing Company

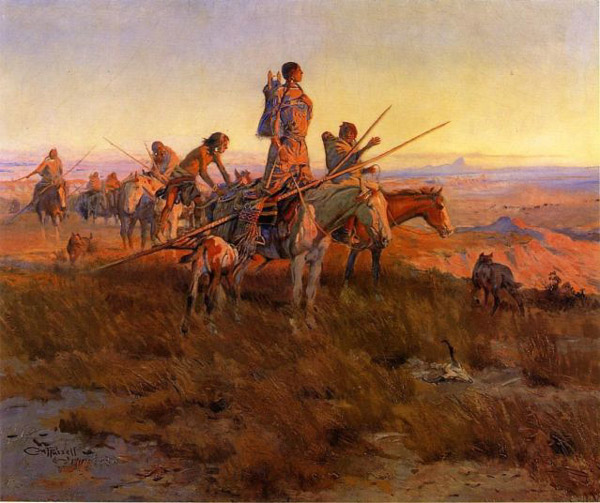

The impact of the decimation of the bison population on the Great Plains Indians was dramatic. As previously noted,

the Inidans upon the Great Plains relied upon the buffalo for sustenance, shelter and clothing.

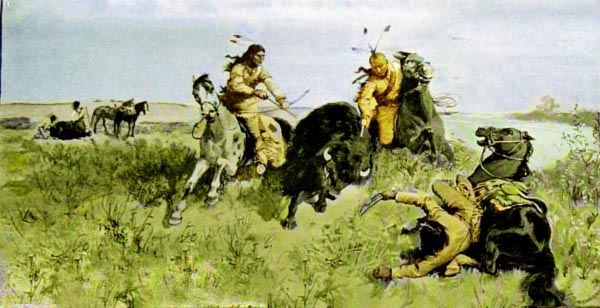

"In the Wake of the Buffalo Hunters," C. M. Russell, 1911

Dixon's biography notes:

The Plains were marvelously adapted to the needs of uncivilized people, who derived their sustenance from the bounty of the wilderness

and to the heavy increase and perpetuation of the animal life upon which they subsisted.

Upon its level floors, enemies or game could be seen from afar, an advantage in both warfare a

nd hunting. The natural grasses were almost miraculously disposed to the peculiarities of soil

and climate, affording the richest pasturage in the green of summer and becoming even more

nutritious as the seasons advanced toward the snows of winter. This insured the presence of

enormous numbers of herbivorous animals, such as the buffalo, the antelope and the deer, from

which the Indian derived his principal food and fashioned his garments and his shelter.

His only toil was the chase with its splendid excitement, and his only danger the onslaught

of tribal enemies. The climate was healthful and invigorating. In all the world could not have

been found a more delightful home for primitive men.

That the Indian should have resisted with relentless and increasing ferocity every

effort to drive him from this paradise was natural and justifiable from his point of view.

In those days, he felt that to go elsewhere meant starvation and death for his family and

tribe. Above all, he firmly believed that the country was his, as it had been from the beginning,

and that the white man was cruel, merciless and wrong in depriving him of his old home—a home

that the white man did not need and would not use.

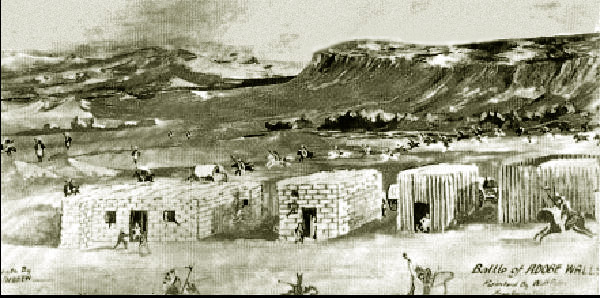

It should not have come as a surprise that one of the first battles of the Indian Wars of the 1870's was the seige of twenty-eight buffalo hunters at

Adobe Walls. Seige commenced on June 26, 1874 and lasted five days.

Battle of Adobe Walls

Adobe Walls was a small outpost intended to serve approximately two hundred buffalo hunters in the area. It consisted

of a store, a mess hall, Hanrahan's Saloon, a blacksmith shop and Rath's hide yard, restuarant and store. The buffalo hunters using their superior

fire power held off some 700 to 1000 Indian under the leadership of Quarnah Parker. Professional buffalo hunters customarily used 45, 50, or larger

Sharps. Dixon managed to get off what he termed a "scratch" shot killing an Indian of a rise about a mile away. In the battle, the Buffalo Hunters lost four.

Ike and Shorty Shadler who were sleeping in their wagon were killed and scalped before those in the

outpost were alerted to the presence of the Indidans. The Shadlers' dog was also "scalped." Billy Tyler who was shot as he was fleeing for the safty of

the store. A fourth accidently killed himself. The Indians killed all of the oxen and 56 horses.

The battle is regarded as the first conflict in the Red River War (1874-1875) It led to a policy of requiring the

Indians to live on Reservations. One day short of two years from the commencement of the Battle of

Adobe Walls that, policy led on June 25, 1876 to a debacle, discussed later, on the Northern Plains at a place called

"Greasy Grass."

"Hunting on the Plains," Currier and Ives.

The above image depicts a Métis rider hunting bison on the western plains of Canada.

Even where the buffalo hunters did not venture, the impact was felt. On the plains of Saskatchewas, the

bison had a distinct migratory pattern which in the summer carried the herds southward across the Medicine Line to the

Upper Missouri and along the Yellowstone. They then returned to winter along the Saskatchewan River.

Gradually, the bison no longer returned to their traditional grounds. In 1878 Monague Aldous, of the Dominion Land Office, surveyed along the

Saskatchewan River. He reported that in one Métis village the inhabitants were dependent upon the buffalo but there was

a realization that the bison would soon be exterminated.

have to turn to agriculture. See report Part II, Appendix to Parliamentary Session Papers, NO. 7, 1879.

Thus, the impact on Métis and British

Indians, such as the Cree, was the same as on their cousins the American Indians.

The threat of starvation as a result of the loss of buffalo north of the Medicine Line ultimately led to the

return of Sitting Bull and his band to the United States.

"Sport of the Past," Image based on 1873 pencil sketch by Paul Frenseny.

It has been repeatedly contended that the extinction of the bison was an intentional policy of the

military to tame the Indian. The argument is almost solely based on a single

passage fron a 1907 book by former buffalo hunter John Cook:

The Texas legislature, while we were here among the herds to destroy them,

was in session at Austin, with a bill drawn up for their protection. General

Phil Sheridan was then in command of the military department of the

Southwest, with headquarters in San Antonio. When he heard of the nature of

the Texas bill for the protection of the buffaloes, he went to Austin, and

appearing before the joint assembly of the house and senate, so the story

goes,

told them that they were making a sentimental mistake by legislating in the

interest of the buffalo. He told them that instead of stopping the hunters

they ought to give them a hearty vote of thanks, and appropriate a

sufficient sum of money to stroke and present to each one a medal of

bronze, with a dead buffalo on one side and a discouraged Indian on the

other. He said: "These men have done in the last two years, and will do

more in the next year, to settle the vexed Indian question, than the

entire regular army has done in the last thirty years. They are destroying

the Indians' commissary; and it is a well known fact that an army losing

its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder

and lead, if you will but, for the sake of a lasting peace let them kill,

skin and sell until the last buffalo is exterminated. Then your prairies

can be covered with speckled cattle, and the festive cowboy, who follows

the hunters as a second forerunner of an advance civilization."

The Border and the Buffalo: An Untold Story of the Southwest Plains (Topeka, Kansas: Crane, 1907

Whether Little Phil actually made such a speech may be questioned. One source indicates that

the alleged speech was give in in 1875. The writer has found no contemporenous accounts of

the alleged remarks. Sheridan had long since been removed as the commander in Texas.

Sheridan did, indeed, serve as military commander in Texas for six months in 1867. For most of that period he was devoted

to assisting Mexicans supporting President Juarez or was headquartered in

New Orleans. At that time, the buffalo was in no way endangered, nor would the quoted lanquage have been used. The term "festive cowboy" certainly

would not have been used. The term "cowboy" was not in common use. In Texas the term used was

"drover" or "waddy." The term "cowboy" when it first came into common use was as a pejorative. Only much later was the word

cowboy utilized in a positive sense. For further discussion of the derivation of the term "cowboy"

see Cheyenne. The mass slaughter did not occur until later. Sheridan

was removed by President Johnson. Gen. Sheridan was later stationed in St. Louis and Chicago. Additionally,

he travelled to Europe in order to observe the Prussian Army defeat the French.

Assuming that the alleged speech was ever given, it is doubtful that it

would have represented official policy. The near extinction of the

bison was more of a matter of some 5,000 buffalo hunters being inspired by old fashioned greed to

supply a public demand for buffalo robes, much in the same manner as the near extinction of the

egret was as a result of the demand for feathers for women's hats, the near extinction of the American elk was as

a result of the demand for elk teeth for fraternal jewelry, and the endangerment of the American alligator was as a

result of the demand for alligator shoes and handbags.

Next page: The beginnings of the Indian Wars.

|