Custer's Last Fight,

1889 Lithograph based on painting by F. Otto Becker, based on 1884

painting by Cassilly Adams

The above lithograph is, perhaps, the most famous view of

of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, referred by Indians as the Battle of

Greasy Grass. It was distributed in the millions as an advertising poster by a

St. Louis brewer. It is, however, as will be discussed later, best charitably described as

fanciful. The Indians' attire is in error; Custer's hair is in error, he had it closely

shorn before leaving Ft. Abraham Lincoln; he is

wearing a red scarf; and, perhaps most importantly, the battle is being fought on the

wrong side of the river. Other versions of the battle depicted on the ensuing pages were even more imaginative.

More has been written of the Battle of the Little Bighorn than any of the other battles on the

Northern Plains, more than the "Battle" of Wounded Knee, the last of the great confrontations. The latter,

however, is much better documented. Photographers were on the immediate scene. The beginnings, however, of the

Campaign of 1876 date back more than 25 years to a point prior to the Civil War. Although, as noted on previous pages,

there had been conflicts between the White Man and the Indian, generally the Plains were

quiescent during the 1850's. Resentment on the part of Native Americans began to build as a result of incidents such as the Battle of

Blue Water Creek in Nebraska and the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado.

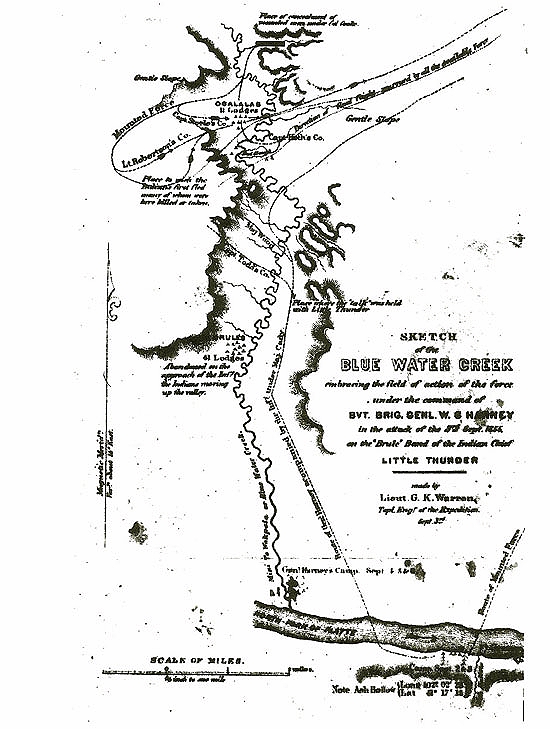

Map of the Battle of Blue Water Creek, drawn by

Gouverneur Kemble Warren, 1855

In 1851, the various Indians were summoned to Ft. Laramie where a treaty was entered into. In 1854, Chief

Conquering Bear with Ogalala and Brule Sioux were gathered near Ft. Laramie to receive promised allotments

of food from the government. The supplies were delayed in coming. At the same time the Hans Peter

Olson Company of Mormons was passing through the area. A sickly, half-starved cow belonging to the

Mormons wandered into the Indian camp. The Indians regarded the cow as

abandoned and accordingly used it to provide sustenance. The Mormons complained to the Military and

demanded return of the cow. A young West Point Graduate, Brvt. 2nd Lt. John L. Grattan, proceeded with

a company to Chief Conquering Bear's camp and demanded that the Indian suspected of the taking of the

cow be turned over to the military. Chief Conquering Bear refused to turn over the suspect but, instead,

in compliance with treaty terms offered compensation in the form of a horse. The horse would, in fact,

have been more valuable that the cow. Grattan refused the offer. the Chief started to walk away when

one of Grattan's men shot the Chief. In the ensuing fire fight Grattan and all but one of his men

were killed. The one had his tongue cut out and subsequently died in the Fort

Laramie hospital. Among those present was a young Indian boy later to be known as

Red Cloud.

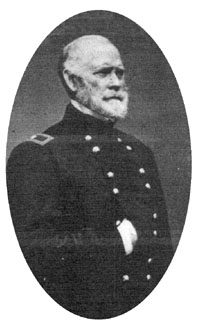

William S. Harney

William S. Harney

The Government determined that the Indians needed to be punished and, accordingly, called Col. Wm. S.

Harney back from Paris where he was then sojourning. Harney had previously served in the Seminole

Wars in Florida. In 1840, he and

32 men were guarding a store at Indian Key. The store was attacked by Chekika and

Billy Bowlegs II. Eighteen of the troops were killed. Harney escaped clad only in his

underwear. Harney organized a unit of 90 soldiers disguised as Indians and

took Chekika and his men by surprise. Harney hanged Chekika and his men. In

retaliation, the Miccosukee medicine man Arepeika ordered all white captives

burned alive. The army ended its practice of hanging Indians. Arepeika was

never captured and died in his 90's in Florida's Big Cypress Swamp.

Thus, An expedition intended to punish the Sioux for the massacre of Grattan and his Company was

organized by Harney. Harney, with a force of 600 men, consisting of the

2nd Dragoons, five companies from the 6th Infantry, one company from the

10th Infantry and a battery of the 4th Artillery came upon

the camp of Chief Little Thunder at Blue Water Creek near Ash Hollow, Neb. When the Indians began to flee, Haney deceived Little Thunder

with a white flag of truce, then surrounded the camp, killing men, women and children. A young topographic engineer, G. K. Warren, reported:

"The sight . . . was heart-rending--wounded women and children crying and moaning, horribly mangled by the bullets." Two dead women

were found clutching their dead children. For discussion of G. K. Warren, see

Hayden Expedition. Among those believed to be present was a ten year old

Indian boy called Curly, later to be known as Crazy Horse. The use of a white flag of truce to

deceive the Indians was a common practice during the Seminole Wars. The great Seminole

chief Osceola was taken prisoner under a flag of truce. The impact of the battle, however,

was than the Indians fearful of similar retribution remained peaceful for the next ten years.

The Battle of Sand Creek

The Battle of Sand Creek

With the advent of the Civil War, Federal forces in the West were reduced. Of those troops who remained many were

volunteer forces rather than professional soldiers utilized before the war. Thus, in

Colorado volunteers were utilized to protect the Territory from both Indians and expected Confederate

invasion from the Confederate controlled Territory of New Mexico. At the commencement of the

war Confederate forces controlled the southern part of present day New Mexico and Arizona. Among the volunteer units was

the First Colorado Volunteers commanded by the "Fighting Parson", Col. John M. Chivington (1821-1894). In 1862,

Chivington's Unit played a significant part at the Battle of Glorietta Pass which ended the

Confederate threat to the gold fields of Colorado.

On November 29, 1864, Black Kettle was peacefully camped along Sand Creek in present day

Kiowa County, Colorado, to the north of present day Chivington. Adjacent to

Black Kettle's lodge flew a white flag and the American Flag. Without warning, Col. Chivington attacked

the village killing or wounding some 200 Cheyenne, two-thirds of which which were women and

children.

Chivington and Harney were not the only ones to treat Indians poorly. James Regan described the hanging of three

Indians at Fort Laramie from the same time period:

[T]he gallows stood in plain view of the post. We could see from the rotten debris that the scaffold consisted of

two ordinary uprights about ten feet apart, connected with the usual cross-piece at the

top. On this gallows three Indians were hung at the same time, and, it would seem,

in a most barbarous manner,óby means of coarse chains around their necks, and heavy chains

and iron balls attached to the lower part of the naked limbs to keep them down. There was no

drop: they were allowed to writhe and strangle to death. But true to the traditions of their

race, they died stoically, and, as the red man always does when driven to the wall, bravely.

Their lifeless bodies, swayed by every passing breeze, were permitted to dangle from the cross-piece

until they rotted and dropped to the ground. We could see their bones protruding from the

common grave under the gallows. The punishment of these Indians was no doubt just, but the

mode of carrying it out was barbarous.

The uproar as a result of the Sand Creek Massacre caused the resignation of Colorado Governor John Evans. Retaliation by the

Indians was not long in coming.

In most areas of the Great Plains along the Overland Trail one may see for long distances. An exception, however, existed in the area east

of Julesburg. About four miles east of Julesburg, the stage road passed through an arroyo. Between the

arroyo and Julesburg is a line of hills which cut the stage road off from view from Julesburg. Julesburg, itself,

had been established in 1859 along the South Platte near its confluence with Lodge Pole Creek. The little town

had been established as a stage station to serve the run between Atchison, Kansas, and

Denver. By 1865, the little town had grown and consisted of the stage station, telegraph office, blacksmith, a stable for fifty horses,

a corral, billard parlor, and a boarding house. To the east of the stage station, was a sod breastwork to protect

the town from marauding Indians. A mile east of Julesburg was a ranch operated by Edwin D. Bulen (1834-1895) which provided

hay to freighters and the stageline. About a mile to the west of Julesburg, a small soddie fort, under the command of Captain Nicholas J. O'Brien (1839-1916),

had been established. The fort was manned by about 40 members of

Company F of the 7th Iowa Volunteer Cavalry. O'Brien would later serve as

a deputy United States marshal for Wyoming and as sheriff of Laramie County (1874-1875). In early January, 1865, unbeknownst to

the occupants of the fort or the stage station, an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 Indians had gathered

out-of-sight from the Fort in the arroyo and in the hills. At about 2:00 a.m., January 7, 1865, 4 miles east of Julesburg, the

westbound mail coach entered the arroyo and was fired upon

by some Indians.

On board the coach was the driver and an express agent. The agent had responsibility for a shipment of money being sent from

New York to Central City, Colorado Territory. The stage, however, was able to make good an

escape from the Indians and proceeded to Bulen's Ranch. There, the the driver and express agent took refuge in Bulen's mud house. With

sunrise, the stage then proceeded on the Julesburg and the fort. In the meantime, a patrol of soldiers

from the fort had discovered some Indians. Thus, another patrol was dispatched to engage the

Indians. Thus, with the fort shorthanded, a request for a military escort on to Denver was refused by

Capt. O'Brien. O'Brien, however, advised the express agent that it was dangerous to proceed and that

the stage should stay at the fort. Instead, the stage returned to the station at Julesburg which was occuped

by three or four persons. The horses were unhitched and placed in the station stable. Fifteen minutes

later, the cavalry patrol was observed being chased by the Indians. There being no time to rehitch the

stage, the driver and express agent each mounted a horse and followed the fleeing soldiers to the

fort. There, the residents of the

town watched helplessly as the town and the stage with its treasure box were plundered. Needless to say,

the consignor of the money was unhappy and sued Ben Holladay, the proprietor of the Overland Stage line. Holladay lost.

See Holladay v. Kennard, 79 U.S. 254 (1870).

On February 2, the ravaging of Julesburg was repeated with the town being totally burned down. During the

plundering of the town, the Indians invaded the telegraph station which in the meantime had been

moved closer to the fort. In the telegraph office the Indians discovered jars of a

liquid which they took to be firewater. In those days, the telegraph was powered by

the Grove battery named after its inventor Sir William Robert Grove (1811-1896). The Grove

cell utilized nitric acid. As the batteries ran down, they had to be replenished by the

addition of more acid. The firewater was certainly potent. It was the acid. With lips, mouths, and

throats burning, the Indians smashed the remaining jars onto the floor where the acid

burned through their moccasins. The Indians dashed out of the telegraph station to do some high stepping dancing. Others went into

the station to determine the problem, but soon emerged performing the same dance.

In what was to become Wyoming, Federal troop strength was reduced along the

Oregon Trail in response to the greater need in the east. Indeed, as later discussed with regard

the the Overland Stage, transportation routes to California were interdicted by the Indians and

roads were moved further south to the southern part of present day Wyomning instead of

the former route along the North Platte.

Fort Caspar

In 1859, Louis Guinard constructed a bridge near present day Casper to compete with an earlier bridge

operated by John Richard near present day Evansville. Guinard's trading post was also used by the

Overland Stage. Upon the completion of the Pacific Telegraph, the facility was also used as

a telegraph relay station In June, 1862, the Army in order to protect the telegraph posted a company

from the 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry at the station.

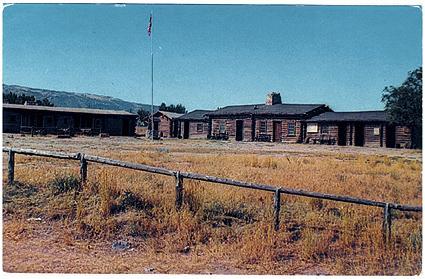

View of reconstructed Ft. Caspar fron end of

Guinard's Bridge. Photo by Geoff Dobson

The bridge allegedly cost Guinard some $40,000 to build. The buildings in the background in the

photo were originally constructed by the Overland Stage. Guinard's residence and the telegraph station

are behind the trees to the right of the photo.

Fort Caspar

In 1865, two battles were fought with the Sioux near present day Casper, one the Battle of the

Platte River Bridge, in which a 20-year old lt. Caspar Collins, was killed, and the

other shortly thereafter the Battle of Red Buttes, when the Sioux attacked

a wagon train coming from Sweetwater Station. Casper is named after Collins. Ft. Collins,

Colorado, is named after Collins' father who was also a military officer. The

reconstruction of Fort Caspar is based on sketches of the fort at the Platte River

Bridge made by Lt. Collins in 1863.

The two battles were described by William G. Cutler in his 1883 History of the

State of Kansas

Cutler sets the scene:The garrison at Platte River Bridge consisted in all of

about one hundred and ten men, including the non-commissioned staff and

band of the Eleventh. About eighty of the number were armed with carbines,

but were now reduced to less than twenty rounds of cartridges per man. Of

the remaining thirty, about half had revolvers, and the others no arms.

The recent demonstrations caused Maj. Anderson grave apprehensions regard to Sergt.

Custard of Company H, who, with twenty-four men of Companies D and H, had

been to South Pass, as escort to a train with supplies for the various

stations, and was now within about twenty-five miles of the station on his

return. On the morning of the 22d, the party came in view on a high hill

about six miles west, apparently unconscious of the presence of Indians

in their vicinity.

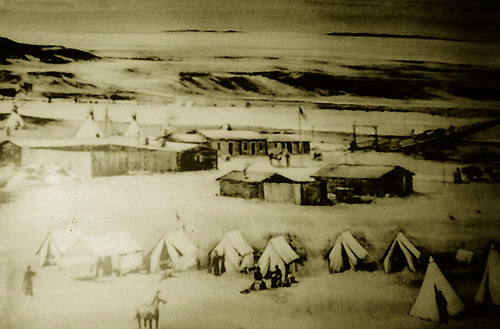

Reconstructed Fort Caspar, 1950's, looking west.

The separate small building on the west end of the parade ground was the commissary.

The left end of the long building was a Barracks. The taller midsection was the

Kitchen and mess. To its right was another barracks. The end section

on the right was the Guinard residence. The end portion later

housed the telegraph office for the Pacific Telegraph.

Reconstructed Fort Caspar, 1950's, looking west.

The separate small building on the west end of the parade ground was the commissary.

The left end of the long building was a Barracks. The taller midsection was the

Kitchen and mess. To its right was another barracks. The end section

on the right was the Guinard residence. The end portion later

housed the telegraph office for the Pacific Telegraph.

Cutler describes the Battle of the Platte River Bridge and the death of

Caspar Collins: The howitzer was fired to warn them of their danger, and Lieut. Collins

with about thirty of the best mounted and armed men of the Eleventh, sent

to their assistance. The Indians remained in ambush until the party from

the station had moved out about half a mile to the first range of bluffs,

when suddenly from the ravines, and woods, and every conceivable hiding

place, 2,000 Indians sprang into view and charged upon the little band

from every direction. There was no hope of going forward, and seemingly

no chance of escape; but after once discharging their carbines, which they

had no time to reload, with no weapons but their revolvers, they fought

their way back toward the station. The party was completely surrounded on

every side, and friend and foe so intermingled in the confused mass of

combatants, that Maj. Anderson was unable to use the howitzer, but all

the remaining available force of his already weak garrison was sent to

the relief of the sorely pressed party. The Indians now turning a portion

of their force against the new enemy, Lieut. Collins' party succeeded in

cutting their way through the host that still beset them, when just as

escape seemed possible, and the worst was apparently over, Lieut. Collins'

horse, maddened by the terrible confusion, broke from the control of his

rider, carrying him straight into the surging crowd of eager, vengeful

savages, to share the fate that befalls every unfortunate foe that falls

into their cruel hands. Of the party, four others were killed, and one

wounded. The rest, as by a miracle, escaped.

Cutler describes the Battle of Red Buttes: Sergt. Custard had, in the

meantime, nearly gained the river, and saw the Indians for the first time,

when the whole host rushed upon him, after their encounter with Lieut.

Collins' party. The men sheltered themselves as best they could behind

their horses until they were shot, and then taking advantage of every

knoll and hillock, for six hours fought with the desperate courage of men

who feared the death of a soldier far less than the horrible fate of a

prisoner. Every one was slain; only three men of the party who were cut

off before the fight began, and who escaped by swimming the Platte, lived

to carry the tale to their sorrowing comrades at the station. The next day,

when the mutilated bodies were recovered, and buried, with military honors

in one grave, every Indian had disappeared from the vicinity, and was

beyond the reach of any punishment which the garrison might be able to

inflict.

With the death of Caspar Collins, the post at the bridge was renamed after Collins at the suggestion

of Grenville M. Dodge. Upon the construction of Fort Fetterman near present-day Douglas, the fort was

abandoned. Some of its materials may have been used in Fetterman's construction. The remainder

of the fort was burned by the Indians.

Music this page:

When This Cruel War is Over

(Weeping Sad and Lonely)

Lyricist, Charles C. Sawyer

Composer, Henry Tucker

I.

Dearest love, do you remember

When we last did meet,

How you told me that you loved me

Kneeling at my feet?

Oh! how proud you stood before me

ln your suit of blue,

When you vowed to me and country

Ever to be true.

Chorus

Weeping, sad and lonely,

Hopes and fears, how vain! (Yet praying)

When this cruel war is over,

Praying that we meet again.

II

When the summer breeze is sighing

Mournfully along,

Or when autumn leaves are falling,

Sadly breathes the song,

Oft in dreams I see thee lying

On the battle plain,

Lonely, wounded, even dying,

Calling, but in vain.

Repeat chorus

III

If, amid the din of battle,

Nobly you should fall,

Far away from those who love you,

None to hear you call,

Who would whisper words of comfort ?

Who would soothe your pain?

Ah, the many cruel fancies

Ever in my brain.

Repeat chorus

IV

But our country called you, darling,

Angels cheer your way!

While our nation's sons are fighting,

We can only pray.

Nobly strike for God and country,

Let all nations see

Slow we love the starry banner,

Emblem of the free.

Repeat chorus

One of the most popular songs during the Civil War, it sold over a million copies.

"When this Cruel War is Over" was also popular with Southern troops, with, however, a slight change of

words.

Next page: Forts Reno and Phil Kearny.

|